|

| The Aizuri Quartet |

Welcome to the New Season! Our first concert takes place at Temple Ohev Sholom on North Front Street in uptown Harrisburg this Wednesday at 7:30pm, with the Aizuri Quartet, the latest recipient of the coveted Cleveland Quartet Award which includes a concert-tour of various venues around the country. In addition to Harrisburg and Market Square Concerts, it will take them to New York's Carnegie Hall and presenters in Buffalo, Detroit, Urbana (IL), Kansas City, Austin (TX) and the Freer Art Gallery in Washington DC.

Known for their advocacy of new music since their founding in 2012, the Aizuri's program here of four 19th Century works might seem rather tame. Yet pairing Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny with Robert Schumann and his wife Clara – or, if you prefer, given the program order, Fanny Mendelssohn with her brother Felix and Clara Schumann with her husband Robert – examines creative relationships as well as personal relationships outside the immediate sound of the music. And it offers us a chance to explore the role of “Composers Who Happen to Be Women” before the mid-point of the 19th Century as well as more challenging and often more uncomfortable issues like Anti-Semitism with the Mendelssohns and the delicate balance of Creativity and Mental Health with Robert Schumann.

These are four works written within a span of nine years. Fanny Mendelssohn's rarely heard String Quartet from 1834 (once could just as easily say “rarely-heard Fanny Mendelssohn and her practically unknown String Quartet”) and one of Felix Mendelssohn's shorter works for quartet, written in 1843, form the boundaries of this program's world. While Felix wrote several quartets of his own, they get performed frequently enough, so lets, for the moment, focus on Fanny.

Clara Schumann, who for various reasons, wrote little music and no string quartets, will be represented by an arrangement of one of her songs. Not just any song: despite its ominous sounding title, “I stand in darkness Dreaming,” it was written at Christmas as a present for her new husband. They'd been married just a few months earlier and had just moved into a new home together, finally, after a long and traumatic courtship (and in this post we'll briefly meet one of the more notorious Stage Fathers in Classical Music, Friedrich Wieck, who opposed his daughter's marriage and fought them in the courts). Robert, missing his wife while she was away on tour in 1842, found a creative outpouring on her return that resulted in a set of three string quartets – his only published quartets – which were first performed in a private reading on his wife's birthday. He'd also dedicated them to their friend, Felix Mendelssohn – the previous year, Mendelssohn conducted the world premiere of Schumann's 1st Symphony – and there any many instances in the piece, particularly the second movement, which show Mendelssohn's stylistic influence. It's seems odd, considering Mendelssohn is only a year older than Schumann, but Mendelssohn was, at this point in his life the better known and more productive composer, not to mention an extrovert to Schumann's introvert.

Most music-lovers may not realize the composers whose music they're listening to lived in Real Time and Space and may well have known each other in professional as well as social contexts. (This in turn makes me think of the first time I ran into one of my elementary school teachers in the grocery store and thought “wow, she eats food?), that they have lives outside of being marble busts or names emblazoned on concert programs and music appreciation textbooks.

And given the way my imagination tends to work, I started imagining all four of these composers, who were at one time or another all in Leipzig at the same time, in a setting kind of like “Friends.”

Before I get too carried away, I should point out, first of all, Felix Mendelssohn's sister, Fanny, remained in Berlin where she and her younger brother had grown up and began their careers, even if hers was confined to the music room of the family home while Felix wandered the length and breadth of Europe as a much celebrated conductor and composer. While Felix was the conductor of Leipzig's famous Gewandhaus Orchestra since 1835 (he was 26 at the time), he did not live permanently in the city, commuting from Berlin or wherever he might have been touring at the time. (What would you call a mid-19th Century jet-setter...?)

Robert and Clara Schumann, recently married, were 30 and 21 years old respectively in 1840 when they moved into their new apartment in a building now known as “The Schumann House”, today currently a museum. But with Robert's health rapidly deteriorating and Clara's international career making demands on their domestic life, they moved out at the end of 1844 to settle in Dresden.

|

| The Schumann House on Inselstrasse, Leipzig |

Felix Mendelssohn, finally, moved to Leipzig full-time in early-1845, finding a 2nd floor apartment in a comparable building now known as “The Mendelssohn House,” but only lived there for the not-quite three remaining years of his life. It too exists as a museum today.

|

| The Mendelssohn House on Goldschmidtstrasse, Leipzig |

Regardless, Clara concertized with Mendelssohn and the Gewandhaus Orchestra frequently in the 1840s, and Mendelssohn premiered several works of Schumann's at the time, including his 1st Symphony in 1841 They occasionally held “read-throughs” (try-outs) of each other's newest compositions, including the set of three string quartets Robert composed earlier in 1842, a private reading intended to celebrate Clara's 23rd birthday and which he dedicated to Mendelssohn. And they were all involved, one way or another, in the founding of a new music conservatory – well, all except Fanny, back in Berlin...

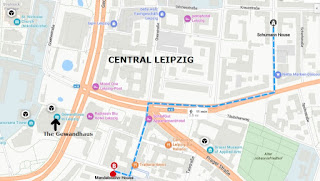

Here is a map of modern-day Leipzig with the Schumann House and the Mendelssohn House marked, only 0.6 of a mile apart. It would be pleasant to imagine them making the 11-minute walk back and forth for a social evening now and then.

Still, the imagination (or at least mine) was fueled by seeing a

restaurant two blocks south of Mendelssohn's home, just beyond the edge of the map, called “The Blue

Zebra” which made me think of Brahms' favorite hang-out in Vienna,

a tavern called “The Red Hedgehog” – except the Zebra is a

modern pub specializing in African cuisine (complete with take-out).

Well, if we're engaging in time-traveling, what would it be like to

stop at the Trattoria Amici around the corner from Mendelssohn's –

on the way to the Schumanns' – for a pizza? Sitting nearby, you

might overhear them discussing, say, news from their latest tours and

performances, or gossip from that immoral cesspool of Paris about

Chopin and his affair with George Sand (“it's said she even wears

men's clothing!”) or just trading anecdotes about the raising of

toddlers in a home where you're trying to compose!

The stuff, perhaps, of Historical Fiction if not exactly Musicology: in actuality, Mendelssohn moved into his new apartment only months after the Schumanns moved out of Leipzig. Still, they had ample opportunities during the early-1840s to meet whenever Mendelssohn was in town; and then Dresden was only a short train-ride away whenever the Schumanns had reasons to be in Leipzig, professionally or socially.

Mendelssohn's new place was conveniently located just a few blocks from the hall where his orchestra performed, the famous Gewandhaus. But Leipzig is also a city haunted by Bach who'd spent most of his career at the St. Thomas Church, located about a mile from the Gewandhaus as the crow flies. Just beyond the church is the famous Mendelssohn Monument, its statue erected in 1892 but pulled down and destroyed by Nazi sympathizers in 1936. It was only replaced by a modern replica in 2008. But that is, alas, one of the more horrible aspects of the History of Art and Humanity which would only make this post even longer and more complicated than it is.

With that, let's move on and Meet the Composers.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Fanny Mendelssohn, long overshadowed by her little brother Felix, was born in Hamburg in 1805. Their father, a successful banker, running afoul of Napoleonic politics, returned to his native Berlin in 1811, two years after Felix was born. There, the two children both showed considerable musical talent and both were supported by their parents. It is often said that Mendelssohn was one of those rare creative artists who grew up in economic luxury, unlike the poverty or economic uncertainty that influenced many other famous composers' early careers.

One advantage certainly was the regular Sunday musicales the family presented for friends and visitors at their rather substantial house which benefited both Felix and Fanny, including the “gift” of a string orchestra hired to perform not only concertos with the brother and sister as soloists – Fanny as pianist, Felix as both pianist and violinist (he even wrote a concerto for violin and piano for them to play with the orchestra) – but also the thirteen “string symphonies” which proved to be Felix's real “on-the-job training” as both composer and conductor. There are reports of him standing on a chair to conduct so the players could all see him.

They studied composition and counterpoint together but apparently the little orchestra was only for Felix: during these years, 1821-23, when Felix was 12-14, Fanny (16-18) wrote nothing beyond her usual songs and short piano pieces except for a Piano Quartet in 1822. Initially, the parents considered Fanny the more musical of the two but their father changed his mind about music as a suitable career for Felix when he began to show not just an increased talent but a dedication to the work it would take to become a professional musician.

And then, as if from nowhere, Felix wrote his Octet for Strings in 1825 when he was 16 and, a year later, the “Overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream.” Many music-lovers are surprised to learn these works, clearly the work of a mature genius and often considered some of the most perfect pieces in the repertoire (admittedly a subjective reaction), were written by a boy in his mid-teens! (I remember one teacher telling me, when I was a student, “amazing works for a boy his age”; and I said, “amazing works for a man any age!”)

But already in 1820, Abraham Mendelssohn had written to his daughter, "Music will perhaps become his [Felix's] profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament."

She herself did not receive any public notice as a composer until 1830 when John Thomson, who had met her in Berlin the previous year, wrote in a London journal praising a number of her songs Felix had shown him. Her public debut at the piano, one of only three known public performances... came in 1838 when she played her brother's Piano Concerto No. 1.

Between 1824 and 1830, Felix published 12 of Fanny's songs under his own name, part of various sets of songs he'd had published. Today, this smacks of plagiarism, but “back in the day” its was the only way Fanny's music was going to be professionally published and made available to a public audience, with or without recognition. When later visiting London and meeting Queen Victoria in London, she told the composer she would sing for him her favorite piece of his, the song Italien. Whether she was amused or not, Felix was delighted to tell her that one was actually by his sister, Fanny; he was delighted to inform Fanny of the anecdote.

In 1846, having been approached by two different publishers in Berlin, Fanny decided, without consulting her brother, to publish a collection of her songs as her Op. 1, using her married name, "Fanny Hensel geb. Mendelssohn-Bartholdy." In mid-August, then, Felix wrote to her "[I] send you my professional blessing on becoming a member of the craft... may you have much happiness in giving pleasure to others; may you taste only the sweets and none of the bitterness of authorship; may the public pelt you with roses, and never with sand." Two days later, Fanny wrote in her journal "Felix has written, and given me his professional blessing in the kindest manner. I know that he is not quite satisfied in his heart of hearts, but I am glad he has said a kind word to me about it." She also wrote to a friend, "I can truthfully say I let it happen more than made it happen, and it is this in particular which cheers me ... If they [the publishers] want more from me, it should act as a stimulus to achieve. If the matter comes to an end then, I also won't grieve, for I'm not ambitious.”

Her diaries curiously lack much reference to her musical life, especially her composing and certainly not in the context of her being frustrated at not being published, a sense I suspect often the result of more recent attitudes and assumptions (“how would you feel...?”) Today, we bristle at comments like her teacher writing to his friend Goethe, already acquainted with young Felix's accomplishments, that Fanny “plays [the piano] like a man.” In those days, it was considered a compliment and something, I guess, extraordinary.

Still, a friend of Felix's wrote, not long after her death: “Had Madame Hensel been a poor man's daughter, she must have become known to the world by the side of Madame Schumann and Madame Pleyel as a female pianist of the highest class."

(Keep in mind, along the lines of artistic context, Emily Brontë published Wuthering Heights under the masculine pseudonym, Ellis Bell; Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, as Currer Bell; and their sister Anne Brontë, Alice Gray, as Acton Bell, each in the year 1847, the year both Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel and her brother Felix Mendelssohn died.)

While Lucy Miller Murray's program notes include a familiar portrait of Fanny Mendelssohn, painted in 1842 by a family friend – that would be the year before Felix composed the “Capriccio for String Quartet” on the program – for the blog, I've chosen Wilhelm Hensel's sketch, drawn in 1829, the year he and Fanny were married after an 8-year courtship (they met when she was 16).

Technically, I suppose, we should refer to her as Fanny Hensel or, at least, Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel. Given other traditions of the day, she would not have legally retained her maiden name after having married.

It was in 1829 that she composed two piano sonatas – or at least part of them. The second, listed as a fragment and sketched in early November, a month after the wedding, was in E-flat and may be incomplete or the last movement may just have been cut out of the notebook. Regardless, two of the three “sketches” for this sonata were later recycled into the finale of the String Quartet of 1834.

This work, No. 277 out of the 466 known works listed in a numerical catalogue, was written between August and October, and signed “F. Hensel.” It's in four movements: an opening Adagio, followed by the scherzo marked Allegretto (not too fast), a Romanze in the manner of a song but very “romantic” in more ways than one, ending with a lively finale in a traditional “bring-down-the-curtain” vein. While it may not strike one as a “great work waiting to be discovered,” it's certainly more accomplished than the work of a modestly talented amateur. However, after hearing a few too many lackluster performances on YouTube, this one, I think, is committed enough to present a compelling case for programming it. And besides, considering this is the only one we know of that she completed, think how her “on-the-job training” might have evolved into a higher level of achievement had she had the support of family and society inspiring her to compose several more?

= = = = = = = – performed by the Selini Quartet

= = = = = = =

It's interesting to imagine how one of the projects they discussed in their correspondence might've turned out. In 1840-41, they contemplated turning the old Norse legends about the Nibelungen Ring into an opera – Fanny thought “the hunt with Siegfried's death would make a splendid finale for the 2nd Act.” Richard Wagner, who'd begun The Flying Dutchman in 1841, only began putting together some ideas for what ultimately became his Ring of the Nibelung in 1848.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Little needs to be added about the musical life of her little brother, Felix. Long considered one of the leading composers of the 19th Century, his career was, despite the “lap of luxury” he grew up in, not all that easy due to the rampant anti-Semitism of the day and the ensuing purge in the 1930s of the Nazi's attacks on what they considered “decadent music” (both anything too modern for their conservative tastes and anything created by a Jew).

While in this post I'm more interested in the interconnected lives of the Mendelssohns and the Schumanns, the role of Fanny Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann as “women composers” is something of a contrast considering we wouldn't usually refer to Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann as “men composers.” Only in the fairly recent years I'd worked in the classical music radio business, we've gone from calling them “women composers” to referring to them as “composers.” At the time, Fanny Mendelssohn's and Clara Schumann's music (indeed, any music by a woman) would likely be dismissed by those who shared Samuel Johnson's 18th Century attitude toward the Lady Preacher, with the quip “no woman has yet matched the level of Shakespeare or Beethoven” to which I'd respond “indeed, few men have achieved that, either!”

Granted, given the opportunity of recognition and a career, Felix Mendelssohn wrote a lot more music we're aware of today. I'd already mentioned two of his teenaged accomplishments, the Octet and the Midsummer Night's Dream Overture, but I also like to point out to music-lovers that one of his most popular works, his “Italian” Symphony – another work I consider close to perfection – was something he never published during his life time. Why? Because he didn't think it “good enough yet”!!! He kept meaning to get around to making some more revisions. Remember the old adage, “There's always tomorrow”? Well, and then one day, there isn't...

So what was Felix Mendelssohn writing when his sister was working on her String Quartet in 1834? In 1833, fresh off one of his many travels, this one to Italy and a stay in Rome where, among other things, he would go drinking and shop-talking with Hector Berlioz then working on his Symphonie fantastique (as Felix wrote home, he felt the need to wash his hands after handling the score). His own experiences became the inspiration for his “Italian” Symphony, the first draft written in 1833 (btw, his 4th Symphony was written after his 5th Symphony, the “Reformation” of 1832, like the 4th also published posthumously; his “Scottish” Symphony, written in 1842, officially the last symphony he wrote, was published as his 3rd Symphony – confused yet?)

|

| Mendelssohn in 1846 |

Technically, the four pieces of Op.81 – again, officially a posthumous opus – were not intended to be a single work, a String Quartet in four movements. While the first three pieces (as published) might make a conceivable unit in E Major–A Minor–E Minor, the fourth, written much earlier in 1827, is in “the wrong key” for a finale: E-flat Major. The grouping is merely a convenient way of solving the problem of what do with four separate pieces found among his manuscripts after he died.

The first time I heard this, still a student and not quite familiar with Mendelssohn's personal story, I thought they were playing the wrong piece: what kind of “Capriccio” is this? First, it begins with a slow introduction – odd, for so short a piece – but once the “fast section” kicks in, becoming an intense sweep of hard-driven counterpoint, I realize it's more of a “Prelude & Fugue,” reminiscent of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier which had been such an important part of the Mendelssohns' childhood.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = =

A year after composing this “Capriccio,” Mendelssohn made a permanent move to a new residence, leaving Berlin, his official residence, to settle in Leipzig. He had been music director of the city's famous orchestra, the Gewandhaus Orchestra, since 1835, but spent much of his time touring, mostly as a conductor and usually including his own music. But as duties in Leipzig become more pressing and he was becoming involved with founding a new conservatory there, he decides to move his family into a spacious apartment in what to us looks like it must've been a palace in its early days. I remember seeing this and thinking “this was their house??” But it turns out Mendelssohn, his wife Cécile, and their three (eventually four) children lived in a 2nd floor apartment that included a spacious music room and a private studio where he could compose. It is now a museum, open to the public.

|

| The Music Room in the Mendelssohns' Apartment |

Fanny, her husband, artist Wilhelm Hensel, and their son Sebastian, continued to live in Berlin, but occasionally visited her famous and busy brother in Leipzig. There were two visits in early-1847 which included get-togethers with the Schumanns. At one of these, Fanny and Clara sat down and compared notes on their recently completed piano trios: Fanny had recently finished hers; Clara's was completed in Dresden the year before. Imagine what it must have been like for both of them to “talk shop” with another composer who was also a woman!

So now let's meet the Schumanns.

- Dick Strawser

No comments:

Post a Comment