|

| The Balourdet Quartet at rest |

Earlier in the pandemic, their October 2020 virtual concert at New England Conservatory included Beethoven's F Major String Quartet, Op. 18 No. 1. Here's the final movement, Allegro molto.

|

| Adam Sadberry, not at rest |

Even though we're barely getting used to the sudden appearance of Autumn this past week, here Adam Sadberry performs one of the works he'll play on Market Square Concerts' program, Katherine Hoover's “Winter Spirits.”

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| Samuel Barber, the night of his Quartet's world premiere |

When he was 26, he met the great conductor Arturo Toscanini in Italy, showed him some of his music, and gained his enthusiastic support. It was Toscanini's idea he should transcribe the slow movement of this string quartet (which he hadn't finished yet) for string orchestra and publish it as a separate piece. Toscanini, who played little American music, not only championed Barber's symphony and his 1937 “First Essay for Orchestra,” he turned the Adagio into a work that would go on to become Barber's most popular and most frequently performed piece.

With a start like that, what kind of future could this young man have in store? Heady times, indeed!

Intended for the Curtis String Quartet's international tour in 1936, Barber dedicated the work to that same aunt who'd been such an early inspiration, Louise Homer and her husband Sidney.

Here's a recording by the Diotima Quartet with the complete score:

As a composer who regarded Barber as one of his favorite composers (I “ran into him” twice in New York – the first time, in Patelson's, that incredible music store near Carnegie Hall, when I turned around in this narrow aisle and there he was; I did the usual fan-gush before I realized I had stepped on his foot...), I've always felt this finale was a let-down, even a “cop-out,” the result of deadline pressures but also the challenge of finding something that can stand up to a slow movement like that! Since Toscanini wisely suggested turning the Adagio into a piece for string orchestra, perhaps it would've been better for Barber to replace it in the quartet with something more mortal? Anything coming after it had a lot to live up to. As did Barber himself.

Through the magic of You Tube, I've found a 1938 recording by the Curtis Quartet of the Op. 11 Quartet Barber wrote for them – which includes the second version of the finale, added in 1937, months after the “provisional” premiere in December of 1936. There was another revision before the work was officially published (though I can't find a specific date for that). In 1943 he “again revised” the finale and republished his Op.11 in the version we hear today.

But listening to this “original” finale might explain the young composer's frustration: this is a recording made in 1938 – with all the sound-issues that implies – but I can't help thinking what Barber, in the center of this photograph with his arms folded, must have felt at the time (where was this taken, in Rome at the Coliseum?).

I'd never heard this version of the finale before. Everything I'd read about it before said Barber “would later revise the finale,” but I hadn't been aware what he really did was no revision: he scrapped the original movement and replaced it with the “reflection” of the opening which, after two substantial movements, is also only two minutes long, giving the impression this monumental slow movement rose up out of the first movement which then, to get from the Adagio's B-flat Minor tonality to the first movement's B Minor, harks back to the opening to round it out. It always struck me as lopsided. Was he forced into this by a retreating intensity of creativity (every composer's worst nightmare) and a deadline that proved more pressure than he needed?

When I'd read Barber was pressed for time and, after completing the Adagio, couldn't finish the entire quartet before the Curtis Quartet's tour – writing in September, 1936, to the quartet's cellist, "I have just finished the slow movement of my quartet today—it is a knockout! Now for a Finale" – I think I understand why, listening now to this “original” finale: anything after that Adagio would be a let-down, and the pressure on the young composer – he was, after all, 26 by then – must have been enormous. Not that I or any of the other critics who may have pointed this out (as many more would do with the Violin Concerto's finale) would call Barber “a weak composer”! Anybody who could write that incredible Adagio is certainly a very good composer – many composers I'd known or met would no doubt give various parts of their collective anatomy to have written something not only that good but also that successful – but not even Beethoven could turn everything he wrote into a masterpiece.

Perhaps, as a former child prodigy still capable of writing easily and receiving confidence-boosting admiration into his mid-20s, Barber had reached that point dreaded by so many brilliant and acclaimed young composers that would turn the habitual effortlessness of his creativity into something unfamiliar – self-doubting hard work – when the elation of the "Nothing-Can-Stop-Me-Now" syndrome turns into something that could.

Curiously, facing the aftermath of one work's success, he was commissioned to write a second string quartet in 1947, but wrote only 17 pages of sketches for the slow movement, before he abandoned it completely.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| Duke Ellington, c.1930 |

Like George Gershwin who learned his craft plugging songs for Tin Pan Alley, Ellington, once he'd turned himself into a jazz band leader in the 1920s, became a master at the 3-minute miniature for 78rpm recordings. Like Gershwin who wrote his break-through Rhapsody in Blue in 1924 and later became increasingly interested in writing “long-form concert works” as a mix of both the classical and jazz worlds, Ellington didn't really get into “extended works” until his Black, Brown & Beige of 1943. It would be the first of several such works he would create, but unfortunately they were never as well received as his shorter jazz works. But since this post-dates the three famous “tunes” included in this suite, we'll save that for some other time.

As it turns out, Ellington was not a composer to sit down and compose something from scratch from beginning to end. In the case of 1930's “Mood Indigo,” the basic tune came from his clarinetist who'd learned it as “Mexican Blues” from his clarinet teacher in New Orleans, so in the “creative sense,” Ellington was more of an arranger here. “I'm Beginning to See the Light,” from 1944 also credits trumpeter Harry James and saxophonist Johnny Hodges for their creative input. One of the Duke's trombonists claimed he created for “the hook” in “Sophisticated Lady” in 1932 for which Ellington paid him $15 but never gave him credit.

Paul Chihara, a composer in his own right, then took these (and other) Ellington hits and arranged them for string quartet in 2008.

Pointing out the various social issues surrounding “women composers” in general with Katherine Hoover and Amy Beach [see below] and mentioning Ellington as the grandson of slaves – I could spend a lot of space on the social aspects of segregation and the jazz music scene during Ellington's career, as well – Chihara, a Japanese-American born in Seattle in 1938, spent three years of his childhood in a World War II internment camp in Idaho. In 1996, he would use some of these memories to compose two works based on that experience.

When I was a graduate student in the early-'70s, I remember being fascinated by several of Chihara's “Tree” pieces like “Driftwood” for string quartet and “Forest Music” for orchestra, plus “Grass” for double bass and orchestra. He was also a prolific composer of film music (one of his composition students, incidentally, was James Horner, who wrote filmscores you might've heard of for Titanic and Avatar). Earning a doctorate at Cornell, Chihara also studied in Paris, like so many American composers, with Nadia Boulanger and also with Gunther Schuller at Tanglewood.

Gunther Schuller, a teacher and highly respected composer of fairly gnarly “contemporary” music as well as a jazz musician and historian, said of Ellington, he “composed incessantly to the very last days of his life. Music was indeed his mistress; it was his total life and his commitment to it was incomparable and unalterable. In jazz he was a giant among giants. And in twentieth century music, he may yet one day be recognized as one of the half-dozen greatest masters of our time.”

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

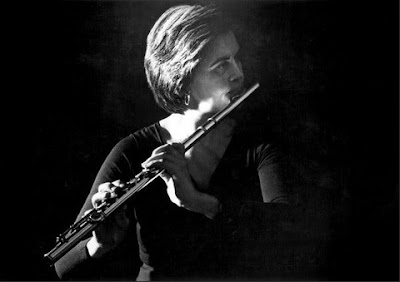

| Katherine Hoover in the 1970s (photo: Jane Hamborsky) |

That “way” was a long and dispiriting process. She first heard Mozart's music when she was 3 and could read music before she could read words. Ms. Hoover started taking flute lessons at the age of 8 – they discovered she had “perfect pitch,” not always a sign of talent, and not always a gift – but her parents discouraged her from pursuing a musical career. Eventually she started an academic degree at the University of Rochester before being accepted into its Eastman School of Music as a flute major and graduating in 1959 with a BS in Music Theory and a Performers Certificate in Flute. She'd also signed up for composition lessons, but, as she told us here in 1987 and said again in an interview in 1996, her composition classes left a bad impression: “There were no women involved with composition at all. [I got] rather discouraged – being the only woman in my classes, not being paid attention to and so forth." Later studies at Yale were one thing but lessons in the early-1960s with Philadelphia-based flutist William Kincaid, she said, taught her more about music than she'd learned from any other composer. In fact, she didn't publish anything until 1972, a set of three carols for Christmas for women's chorus and flute.

John Corigliano, one of America's leading composers around the turn of the 21st Century – would one ever refer to him as a “man composer”? – wrote "Katherine Hoover is an extraordinary composer. She has a wide and fascinating vocabulary which she uses with enormous skill. Her music is fresh and individual. It is dazzlingly crafted and will reach an audience as it provides interest to the professional musician. I do not know why her works are not yet being played by the major institutions of this country, but I am sure that she will attain the status she deserves in time. She is just too good not to be recognized, and I predict that her time will come soon.”

|

| Maria Buchfink: Kachinas |

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Like Katherine Hoover's Native American-inspired flute solo, “Winter Spirits,” Amy Beach's set of variations uses her own song, ‘An Indian Lullaby,’ for a theme followed by six variations. It was written in 1916 – making it, incidentally, the oldest piece on the program – when... well, let's get to that later. How did a woman in the United States of that era get to the point this work was published as her Op. 80?

A child prodigy – perhaps the term “infant prodigy” would be more appropriate here – Amy Cheney could sing forty songs accurately by age one, improvise countermelodies a year later, and by 3 had taught herself to read. She composed three waltzes for piano when she was 4 (take that, Mozart), though, according to a 1998 biography, her mother “attempted to prevent the child from playing the family piano herself, believing that to indulge the child's wishes in this respect would damage parental authority.” As a result, she didn't begin actual piano lessons until the ripe old age of 6 and shortly began giving public recitals of works by Handel, Beethoven, and Chopin, along with a few of her own pieces. Her parents declined offers from agents who proposed arranging concert tours for her.

All this had happened while growing up in New Hampshire. Moving to Boston in 1875, it was suggested Amy, now pushing 8, enroll in a European conservatory, there being no American school where she could study (it was standard in those days, budding American composers going to Germany for their musical training, but it was in the fall of 1875 John Knowles Paine was appointed the first professor of music at Harvard, turning his “fluffy” electives of music appreciation (without credit) into offerings of theory and composition classes as well as, eventually, private instrumental lessons leading toward a music degree, the first music department in an American university, but I digress...). Again, the family declined and found her local teachers including, by the time she was 14, for harmony and counterpoint, the closest she ever got to formal instruction in composition. Otherwise she was self-taught, collecting any book she could find relating to harmony, composition, and orchestration (with no suitable work available in English, she translated Berlioz' treatise).

Then came her debut as a piano soloist with the Boston Symphony in October, 1883, when the 16-year-old girl performed the 3rd Piano Concerto of Ignaz Moscheles (now largely forgotten, he was one of the leading virtuosos of the 19th Century and a teacher of Mendelssohn's) – and played it to a generally enthusiastic audience. She also was the soloist in the Boston Symphony's final concert of the 1884-'85 Season.

Then came her marriage to Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, a prominent Boston surgeon 24 years her senior: she agreed "to live according to his status, that is, function as a society matron and patron of the arts. She agreed never to teach piano,” to limit her public performances to two recitals a year, and to focus on composition rather than performing (though, like most 19th Century virtuosos, whether Moscheles or Paganini, she considered herself a performer who composed her own music). Because it was unseemly for a married woman to have a male tutor, she must continue to teach herself. And she became the composer known as Mrs. H.H.A. Beach.

|

| Amy Beach in 1908 |

Looking back in 1942, she described married life as a happy one (officially, she put it “I was happy and he was content”). But she was also active as a composer: look at some of her works and their premieres. Her Mass in E-flat, written in 1892, was performed by Boston's Handel & Haydn Society. Her Gaelic Symphony, a New Englander's response to Dvořák's “New World,” was premiered by the Boston Symphony in 1896 to great success. She became famous, later if not then, as “the first American woman to have a symphony premiered by a major orchestra” (which begs the question, “were there other American woman who had symphonies premiered by minor orchestras?”). A prominent Boston composer, George Whitefield Chadwick, wrote to her of his enthusiasm for her symphony, adding that "I always feel a thrill of pride myself whenever I hear a fine work by any of us [his colleagues in the 2nd New England School of Composers], and as such you will have to be counted in, whether you [like it] or not – one of the boys." That same year, she was the pianist for the premiere of her Violin Sonata with the orchestra's concertmaster, having already played the Schumann Piano Quintet with him and other members of the orchestra. In 1900, she again appeared as soloist with the Boston Symphony for the premiere of her Piano Concerto in C-sharp Minor.

When her husband died in 1910 – and her mother seven months later – Mrs. Beach went to Europe to rest but noticed the “Mrs. H.H.A. Beach” confused the Germans so she re-styled her name as Amy Beach. And shortly, she resumed her career as a performer, including standard recital repertoire as well as her own pieces, receiving considerable success for her songs (though many German critics found them “kitschy”) and the Violin Sonata. Again, the image I had received in the 1970s, that “as soon as her husband died, she was back to performing and composing,” was simply not true, though she did a good deal more of it simply because, now, it didn't have the restrictions of her husband's social expectations. And curiously, once she returned to the United States and was being asked if she, Amy Beach, was the daughter of Dr. H.H.A. Beach, she changed her name back to Mrs. H.H.A. Beach and remained so until her death in 1944 at the age of 77.

Her reputation has seen a similar shift. While acclaimed, success was not unanimous (but then one could say the same of Beethoven). She published over 300 works including a vast amount of four-part anthems for St. Bartholemew's Episcopal Church in New York. Her publisher complained to her (when, I'd be curious) her “choral pieces had practically no sale.” One of them, however, found its way into the library of a church in Lewisburg, PA, where a college classmate of mine from Susquehanna University had pulled it out for a read-through when I was in the choir. I'm sorry to say there was a great deal of snickering from the choristers and, try as we might, we put it aside as “impossible to sing with a straight face.” I really have no recollection of why exactly beyond it's cloying chromaticism, but as a result my first reaction to Mrs. Beach's name was one of “amateur.”

But at the time, I'd heard little if any of her “other” music, and the same could be said of the average American concert-goer: who, then, had heard her symphony or the piano quintet? True, much of the shorter piano pieces, mostly with picturesque, often cloying titles (typical of the time), fell into that generic turn-of-the-century category of “sentimental salon music,” suitable for amateur performance by the young ladies of genteel households. But the same could be said of Beethoven if all you were judging him by was, say, Für Elise... pretty? Yes, but great music...?

|

| Amy Beach's 10 Commandments (1915) |

As for her Flute Quintet, a set of six variations on a theme, it was written in 1916, shortly after she returned from Europe as World War I was starting (she had delayed her return trip until the last minute and ended up having a trunkful of manuscripts, all works she'd composed during her years of traveling and performing, confiscated at the Belgian border – did they think they were secret a code and she was a German spy? She did express pro-German opinions but, she later admitted, it was for the Culture of Beethoven and Goethe rather than the militaristic Empire of the Kaiser – and it took her 15 years to get them back!). Visiting an aunt in San Francisco, she was commissioned to write something for the equivalent of a “Pan-American Fair” and supplied them with this 20-minute work. Described by critics looking to compare her style to music people might know found references to Debussy and Ravel's quartets (which, written in 1893 and 1905, were, technically, still “contemporary” music) – before, she'd been compared to Brahms and later to Rachmaninoff – even to the point the flute's entrance, after the Theme, was straight out of Debussy's 1894 “Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun.”

Around the same time, she'd begun work on her string quartet which she didn't publish until 1929, reworking it during a stay in Rome. She took three themes from a book on Alaskan Inuit music and integrated them into a fairly spare texture lacking traditional tonal elements and non-standard scales. It would certainly bear little resemblance to anything she'd written before.

The worst thing that could happen to a composer came in the 1920s when she was told her music was now considered “old-fashioned.” But then, the same thing could be said of Bach or Brahms, Rachmaninoff and Samuel Barber; as well as Rossini and Sibelius who, as a result, stopped composing.

But Amy Beach?

She persisted... and continued to compose right up until her death in 1944.

P.S. - As we begin the season with her 1916 "Theme & Variations," Market Square Concerts will end the season on April 29th with "Stuart & Friends" and another work by Amy Beach, her Piano Quintet of 1907, along with the Viola Sonata of Rebecca Clarke and Jennifer Higdon's Piano Trio.

–

Dick Strawser