|

| The Israeli Chamber Project, 1st Rehearsal for Nov. 2022 American Tour |

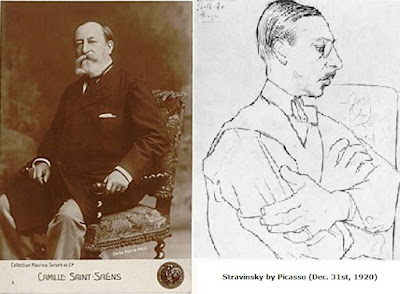

The rest of the Israeli Chamber Project's program, “Saint-Saëns Meets Stravinsky” (read more about that in my earlier post) consists of two

other composers, Maurice Ravel and Arnold Schoenberg.

Certainly, Ravel had an association with the older French master and a friendship with the younger emigrée upstart from Russia. On another hand, Schoenberg, a native of Vienna who spent much of his early career in Berlin, may seem (as usual) the Odd-Man-Out here, had little association with the composer of “The Swan.” He and Stravinsky, however, had throughout their careers a stylistic rivalry despite the fact, later on, they were neighbors in, of all places, Hollywood.

= = = = = = =

[Note: By way of disclaimer, these posts are generally intended to provide historical – or as I like to think of it as “biographical” – background to the music you'll be hearing on MSC programs. Unfortunately, I spent way too much time working on the first post to complete this one well enough in advance of the concert. However, where program notes, briefer by nature, are intended to give you the basics before you hear the music, these posts take the place of “pre-concert talks” which usually run a half-hour or so, and are meant to give you more in-depth insights to the music, usually in some historical context. As usual, if you don't have a chance to read this beforehand, it's always something you can come back to after the concert, and listen to the video links to refresh your ear.]

= = = = = = =

This program consists of five works by four composers from two countries, all written between 1905 and 1918. Ravel's “Introduction & Allegro” which closes the first half of the concert, following Saint-Saëns' Fantasy for Violin & Harp and Stravinsky's Suite from L'Histoire du soldat, is actually the “oldest” work chronologically, predating both the Saint-Saëns and Schoenberg's “Chamber Symphony” that follows it on the second half.

Without going into the history of the harp (which goes back to 3300BC, give or take), Ravel's work came about through a commission from the Erard Company, makers of pianos and harps since the late-18th Century, and was, initially, a tit-for-tat response to the rival Pleyel Company's commission of Claude Debussy to write a work – his Danses sacrée et profane – in 1904 to showcase their new “chromatic harp.” Erard wanted to promote their new line of “double-action pedal harps” (imagine Debussy and Ravel, two of the leading modernists in France at the time locked in a competitive ad campaign!)

For some chronological context, here, Saint-Saëns composed his Fantasy for Violin & Harp in 1907, but he'd already composed a fantasy for solo harp in 1893, written as an “examination piece” for the Conservatoire de Paris (which meant that every harp student competing for a prize that year would also be judged on how well they played this new work). Later, he would compose an additional work for the harp, a Morceau de concert (or “Concert Piece”) in 1918 that was a brief concerto-like work for harp and orchestra. But curious – no? – that neither Pleyel nor Erard chose the 70-something Grand Maître to present its new models, but rather two young upstarts, Debussy who was 42 and following the success of his opera, Pelleas et Melisande two years earlier, and Ravel who, just turned 30, was still a student at the Conservatoire.

The creative process for Ravel, student or not, was slow and painstaking. But this commission was finished, for him, at “break-neck speed.” The impetus was not so much the deadline (if there was one) but the fact he was going on a holiday with friends and wanted to get this thing off his plate. As he wrote a friend, he spent “eight days of relentless work and three sleepless nights enabled me to finish it, for better or worse. Right now, I am relaxing on a marvelous trip.”

This may account, between the speed and his apparent lack of artistic conviction, for the observation several writers have made about the Introduction & Allegro being a step backwards from the advance in his style from the String Quartet of 1902 (a masterpiece regardless of its having been written by a student) and the Sonatine, written along with the suite of piano pieces, Miroirs, between 1903 and 1905. Perhaps this had to do with the lack of time to focus on any challenging stylistic details as much as it had the nature of the commission, with Debussy's example as a model rather than something to be out-done, or of the harp itself.

Whatever the limitations, conscious or otherwise, Ravel placed on its inception, the work has become one of the staples of the harpist's repertoire. Here is a performance by the Israeli Chamber Project with harpist Sivan Magen from 2010:

Like his own teacher, Fauré, Ravel was concerned his pupils find their own individual voices and not be overly (or perhaps overtly) influenced by established masters. For instance, he warned one it was impossible to learn from studying Debussy's music, not because of any antipathy for his elder colleague's music but because “only Debussy could have written it and made it sound like only Debussy can sound.” When an American fan, George Gershwin, a newly minted composer of Classical Music with his Rhapsody in Blue. asked to study with him, Ravel declined on the basis it would get in the way of his already natural talent and turn him into a second-rate Ravel.

One of the things Ravel told his students: “Complexe mais pas compliqué.” Complex, but not complicated. It may sound contradictory, but perhaps the reason he took so long before he completed a piece was because it is easy to write something complex, but difficult to keep it from sounded complicated.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Let's come back to Ravel's Tombeau de Couperin which concludes the program. It would make sense, two works by one composer, to consider them attacca but in this case, given the nature of the programming, let's follow the chronological lead of stylistic development in these pieces from the early years of the previous century. Keep in mind the “newest” piece on this program, the Stravinsky, still often thought of as “contemporary music,” is 104 years old.

Arnold Schoenberg, supposedly when asked if he was Arnold Schoenberg, said “Well, somebody has to be...” With Hallowe'en now past, there are few composers in the repertoire whose presence on a program may frighten your average concert-goer. And while much of the music of his maturity is often a challenge to understand.

Going back to Ravel's “complexe mais pas compliqué,” this is often a criticism leveled at Schoenberg, that he was complex but didn't succeed in sounding “not complicated.”

Perhaps the problem is with the performers who do not understand the music well enough to play it so it doesn't sound complicated?

One of those moments when I knew a student of mine was on the right track (it is nothing I can attribute to my doubtless brilliant teaching) was at a piano recital by a visiting virtuoso, a pianist with a brilliant career (and so shall remain nameless). I was sitting in front of her, a singer who was, like many sophomores, struggling with the sordid details of harmony, as our pianist opened the program with Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata. Three bars into it, she'd leaned over to a friend sitting next to her and whispered with projection worthy of a mezzo, “This is going to be awful...” Perhaps it was because the pianist was bored with playing this belovéd warhorse again or he was bored to be at this small New England college, stuck between concerts in Boston and New York, or whatever – certainly a proficient pianist given the performance but just “not very compelling”. And my student was right: that whole first movement brought to mind a young girl trotted out to play her latest piece for some visiting aunts.

And that is the way I often hear much of Schoenberg's music played, whether through lack of conviction or of sympathy or merely because, beyond the music they're more familiar with, they don't understand what it is that makes this music tick!

"It is brain music," critics complain. It's the result of a “system for composing with twelve notes” – call it serial or think of it as “atonal” – that turns the “compositional process” into the equivalent of a cross-word puzzle (that very word, process...). But, I'm sorry to say, the Tonality we're familiar with from the days of Vivaldi and Bach to Mozart and Beethoven to Wagner (and after that it gets a little fuzzy...) is also a “system” with its own rules and expectations: chords, built a particular way, move in specific ways and while you might argue about things like “parallel fifths,” many of these “rules” are there for a reason, “to create a consistency of sound.” The idea of digressing from a tonic key – D Major, say – leads one to expect, according to the age-old tradition, it should return to that tonic key, resolving the “drama” (real or implied) of its digression and the resolution of the tension that creates.

But too many performers have been unable to apply those same underlying constructs – the skeleton of a musical style rather than the surface language that makes it recognizable as Mozart or Brahms – to composers like Schoenberg. Yes, of course, this “system” allowed a lot of composers without talent the opportunity to produce a lot of bad music, much in the same way those thousands of forgotten composers from the 18th and 19th Centuries did with that system called “Tonality.” A lot of composers who could follow the rules didn't always create compelling art, little more than craftsmen following a blueprint to make a basic chair.

This “craftsman” idea was something frequently thrown at Saint-Saëns – I think I belabored that idea in my earlier post – and yet maybe we don't find anything wrong with much of the music he “crafted.” Yes, some of it may not be as good as Beethoven or Wagner, by comparison, and he may have been derided as the composer of the (in)famous “Wedding Cake Waltz” but by the same token, not everything Beethoven wrote was a masterpiece, either, and similar complaints have been leveled at his Wellington's Victory or his equally frivolous Rage over a Lost Penny, not what you'd expect from the composer of the 9th Symphony.

So, allow Exhibit A in “The Case Against Schoenberg,” this performance of his Chamber Symphony in E Major, Op. 9 by the Israeli Chamber Project:

Written in 1906, this is a work originally for 15 instruments, a rather unusual if unbalanced combination of 10 winds with 5 string-players. Schoenberg's former student and devoted disciple Anton Webern made two arrangements of the piece for more practical considerations, one for the same ensemble needed for Pierrot Lunaire (probably intended to facilitate they're being performed on the same concerts) and another for a standard piano quintet. In this video from 2012, the Israeli Chamber Project performs a conflation of the two, substituting a second violin for the flute; they'll be performing the arrangement with flute on this tour.

The main point to listen for, however, is not so much how different it sounds on the "surface" from the music you might be more familiar with – say, the first of the Brahms serenades which was originally a nonet for strings and winds – but how it may have similar underpinnings with a typical “Romantic” sense of general phrase structure and harmony, not to mention the use of “unity and variety” with the basic material, and especially the often dramatic role played by contrast and the building-up and releasing of tension.

Historically, Schoenberg didn't

“invent” the idea of 12-Tone Music or “serialism” (a term he

disliked) – this in itself is another book-length feature – until

the 1920s. His most famous work, the settings of poems for speaker

and chamber ensemble, Pierrot Lunaire,

is not yet serial but it is

atonal – that is, lacking a sense of traditional tonality achieved

in a traditional, harmonic way – and he only started working with

atonality in the last two movements of his 2nd

String Quartet in 1908. That was still two years in the future from

this Chamber Symphony. Though its concept of “E Major” may be a

bit loose – despite the standard key signatures, the plethora of

accidentals makes you wonder “why...?” – it is still rooted, at

heart, to the same rules (let's call them, by this post-Wagnerian

era, “tendencies”) that led Beethoven to stretch beyond his

teacher Haydn, or, for that matter, for Ravel to push beyond Fauré

and in the generation before him, Saint-Saëns.

Given Schoenberg's eventual directions through this period, it would be interesting to pursue a “Stravinsky Meets Schoenberg” program: aside from the fact their rivalry endured much of their lives, they ended up living not far from each other in Hollywood during the 1940s, and that eventually Stravinsky who, as he'd done with The Rite of Spring before, had taken the Neo-Classicism of L'Histoire du Soldat about as far as it could go (with Neo-Bach in “Dumbarton Oaks” and Neo-Tchaikovsky in The Fairy's Kiss and Neo-Handel in The Rake's Progress) before he discovered that maybe there's something to this serialism of Schoenberg's after all, and his last works embrace yet another approach to how one can organize these twelve pitches of a chromatic scale – and yet still manage to sound like Stravinsky.

But, as I said, that's for another book...

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Back to Couperin – or, rather, Ravel and the long shadow cast by a great name from France's glorious past.

First of all, for non-French speakers (like me), the Tombeau of the title is not a “tomb” in the English sense but more a kind of memorial tribute (beyond a simple tombstone). (Someone once confused it with Tomber which means “to fall” and somehow came up with “The Fall of Couperin”!) And it's a memorial piece on a different level, with each movement dedicated to a different friend killed during the course of World War I (in one case, two brothers killed by the same shell). It is not, thinking of that, a somber piece, nor did Ravel attempt to create musical portraits either of his grief or of the friends themselves: the music is decidedly unmournful and when asked about this, he said “The dead are sad enough in their eternal silence.”

|

| Ravel, at the front |

His mother died in 1917 which only added to his sense of despair, being in the midst of the fighting, dealing with friends who were dying around him, not to mention his own health, but also the fear over the fate of his country and its culture at the hands of the invading Germans.

In that sense, though the music may sound light-hearted, the idea of paying tribute to France's musical past in the name of François Couperin was a way of expressing his “pride of nation.” He created his own suite of dances in the manner of the early-18th Century Couperin, a string of abstract dance movements typical of the standard Baroque instrumental suites. As the war progressed, he would write one, then another, and then eventually by 1917, complete the set.

In 1919, Ravel would then orchestrate all but two of the original piano pieces. It has since been arranged by various people for various combinations. While there isn't a video of the one the Israeli Chamber Project will perform – made by Yuval Shapiro, a member of the Israel Philharmonic's trumpet section – here's a performance of the complete piano original with Jean-Yves Thibaudet, with score:

There are six movements:

In addition to the textures – the overall sound but especially the textures here are very different from what he'd composed nine years earlier – you'll find little nods to Baroque style in the treatment of the hands as if reminiscent of the harpsichord, and in the occasional “ornaments” or appogiaturas in the melody paying an homage of its own to the numerous types of ornamentation used by French composers from the Baroque. We often categorize Ravel, along with Debussy, as “Impressionists” after the style of painting in France at the end of the 19th Century, but that was only a limited influence (certainly one can find it in the Introduction & Allegro) but if anything, Le Tombeau de Couperin is unabashedly Neo-“Classical” – and yet how different it sounds from the neo-classicism Stravinsky was evoking in his own piece written a year later, L'Histoire du soldat.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

It would amount to a scandal not to mention the three scandals associated with our three Modernists on this program. I'd already described the wild premiere of The Rite of Spring, but Ravel's Introduction & Allegro was composed the same year he was involved a scandal of his own.

Already an established talent, Ravel was still studying with Fauré at the Conservatoire and had applied for the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1900 and was eliminated after the first round. He tried again the next year and got 2nd Prize. For the next two years, he won nothing (he was accused of writing works so academic they were judged to be “parodies” and that Ravel must have been making fun of them), and in 1905 he was again eliminated in the first round. Considering he had already written his String Quartet, it seems illogical to argue he was not a “good composer” so it must have been the conservative attitudes of the judges no matter how successful the young composer may have been.

At any rate, given that and the fact Ravel was now 30, even his detractors (including Eduard Lalo) thought this treatment was unfair and unjustifiable. Somehow this ended up in the Press and the furor escalated when it was discovered all those selected for the final round were students of one senior professor who was on the jury and, needless to say, his insistence this was merely a coincidence, did not sit well with anyone. Apparently this became a national scandal and eventually the director of the Conservatoire, Théodore Dubois, was forced to resign and Gabriel Fauré, perhaps the most eminent name on the faculty, was appointed by the government to carry out a “radical reorganization” of the Conservatoire. (Not that it seemed to matter, but Fauré was also Ravel's composition teacher.)

While not quite the same as all the screaming and fisticuffs witnessed at the premiere of Stravinsky's ballet, Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony has its own scandal to account for. Now, you'd assume Schoenberg was not inexperienced when it came to negative reviews and audience disapproval, but just two months before The Rite of Spring's premiere, a concert singular enough to warrant being called the “Skandalkonzert” ended up in an out-and-out brawl!

The program, with the orchestra conducted by Schoenberg, began with Webern's Op. 6 Orchestral Pieces, followed by four Zemlinsky songs, Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony, and then two of the five Altenberg Lieder by Alban Berg, setting poems of a poet prominent in Viennese modernism. (You can hear the second of the two songs performed at this concert here, with no less than Renee Fleming and Claudio Abbado.) Apparently, that's when rumblings of discontent with the earlier music finally boiled over.

Whatever some people thought of the music, it quickly escalated as Schoenberg's followers and fans of modernism retaliated, opponents yelling back and forth, throwing things, destroying furniture, “disturbing the performance” (indeed!) and so on. A composer of operettas who was in attendance testified at the trial – “at the trial”! – the assault of one of the concert's promoters on a concertgoer resulted in a slap (another source says “punch”) so loud it was “the most harmonious sound of the evening.”

| |

| Skandalkonzert! (in Vienna's Die Zeit a few days after the March 31st, 1913 concert) |

And people say Classical Music is dull...

– Dick Strawser