|

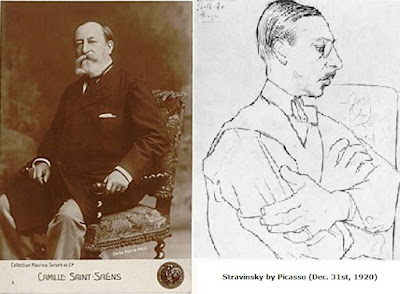

| Saint-Saëns (c.1900) & Stravinsky (1920) Back-to-Back (or not seeing eye-to-eye) |

Who: The Israeli Chamber Project

What: “Stravinsky Meets Saint-Saëns” (as two other giants of the Early 20th Century look on: Ravel and Schoenberg): Camille Saint-Saëns' “Fantasy for Violin & Harp;” the piano trio arrangement Igor Stravinsky made of his L'Histoire du Soldat (The Soldier's Tale); Ravel's Introduction & Allegro for Harp, String Quartet, Flute & Clarinet, plus an arrangement of his Tombeau de Couperin; and Arnold Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony No. 1 in an arrangement for an even smaller chamber combination by his pupil Anton Webern.

When & Where: Thursday, November 3rd, 2022, at 7:30 at Market Square Church in downtown Harrisburg, the first performance in their American Tour (from here to Philadelphia, Washington DC, New York City, Kingston (Ontario), and Detroit)

|

| The Israeli Chamber Project (Photo by Yael Ilan) |

(This post is about the two composers of their program's title, “Stravinsky Meets Saint-Saëns.” The works by Ravel and Schoenberg will be the subject of my second post.)

In Thursday's concert with the Israeli Chamber Project, there are five works by four composers written between 1905 and 1918, a span of only 13 years, first heard when the lush Romantic style of a by-gone age was being replaced by something new and, to those unwilling to give up the comfortable familiarity of the past, different. And surprisingly, among those composers' names, the one we might assume to be the “oldest” piece on the program is the third in order of composition, but by a composer who'd been born only eight years after the death of Beethoven.

Camille Saint-Saëns presumably wrote his first piece at the age of 3, gave small private recitals when he was 5 and made his debut playing a Mozart Concerto five years later (famously offering any of Beethoven's piano sonatas as an encore, played from memory). He became one of the more acclaimed composers of his day, even if his fame and popularity did not always endure into his old age. Many of his colleagues regarded him as “more proficient than inspired,” a prolific composer with many great works but not necessarily enough to make him a great composer (there's a difference). He died at the age of 86, not long after completing a series of sonatas for solo wind instruments and had recently given a piano recital, his playing “as vivid and precise as ever.”

I'll get to Saint-Saëns' reputation after you've had a chance to hear the work on this week's concert.

The Fantasy for Violin and Harp, Op.124, was written in 1907 when he was 72 years old, two years after Ravel composed his “Introduction & Allegro” which concludes the first half of the program, and six years before the premiere of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring.

He was on holiday along the Italian Riviera when he was approached by two sisters, harpist Clara Eissler and her older sister, violinist Marianne, who asked him if he'd write a piece for them. So he did.

It's not meant to be “great music” but it also doesn't descend to the dismissible level of “salon music” with a collection of pretty tunes strung together with simple textures and charming effects. Clearly, judging from the demands on the performers' skills, they were not amateurs playing in the hotel dining room (though they might have been since even good musicians need to make a living somehow). It's not something for violin and piano where the harp is substituting for the “piano accompaniment” (which happens often enough), but a work for two instruments treated equally. And since it's a “fantasy” with its free-flowing implications, it's not meant to be as “serious” as a sonata with a set pattern of movements, even though there are segments that sound like they could be. Contrasts abound, not the least of which is the final dance, a kind of Baroque-style fandango over a repeating pattern in the bass, which, rather than building to a climax, ends on a note of undisturbed pleasantness.

Here are violinist Itamar Zorman and harpist Sivan Magen – members of the Israeli Chamber Project who'll be performing this work on Thursday night – from a 2008 concert in Tel Aviv with Camille Saint-Saëns' Fantasie for Violin & Harp, Op.124:

It's interesting to note the following year, the risk-averse Saint-Saëns, a conservative in an age rapidly developing in new directions with the end of a comfortable old century, wrote music for The Assassination of the Duc de Guise, one of the first films to feature an independent film score by a major composer. Old dog he may have been, but he was still capable of learning some new tricks.

= = = = = = =

There's a famous anecdote that Hector Berlioz, then better known as a writer about music than as a composer, had said of Saint-Saëns, “He knows everything but lacks inexperience.” This specifically pertained to his failure in 1864 to gain the coveted Prix de Rome a second time (one could point out that neither of those who'd won those years is remembered today except on lists of winners of the Prix de Rome). However, Saint-Saëns, in his old age, recalled this comment being made about him when he was 18 and it was Gounod referring to one of his early symphonies. (For that matter, Massenet had been the subject of the joke when Auber told Berlioz in 1863, “He'll go far, the young rascal, when he's had less experience.”)

One of the great honors for a French artist would be his election to the Institut de France (consider it a “hall of fame for smart people”). He failed to gain admittance the first time, being beaten out by Massenet, but was elected three years later. While he had championed “contemporary music” when he was young teacher – then, Liszt and Wagner, understandably, but even Schumann in those earlier years – he had a dimmer view of the New Music of his old age. He succeeded in blocking Debussy from the Institut in 1915: “We must at all costs bar the door of the Institut against a man capable of such atrocities,” referring specifically to his recent suite for two pianos, En blanc et noir. This was a time when World War I was well underway – and Debussy was already ill with cancer.

Perhaps Saint-Saëns' most famous reaction to Modern Music happened in 1913 at the premiere of Igor Stravinsky's (in)famous ballet, The Rite of Spring, when, shortly after the work began, he got up and stomped out of the auditorium. Of course, easily recognized as the Grand Old Man of French Music (and a leader of the Conservative Aesthetic), everybody at the performance would have gotten the message.

However, Stravinsky remembered it differently. After all, he'd been sitting in the audience at the start of the performance and said later that Saint-Saëns was not at the ballet's premiere but at the first concert performance of the orchestral score, not the ballet. While people often excuse the riot associated with the disastrous premiere as having been inspired more by Nijinsky's avant-garde choreography than Stravinsky's music, this doesn't excuse Saint-Saëns: afterward, without the potential distraction of the dancers, Saint-Saëns was convinced Stravinsky was insane.

In 1918, responding to Darius Milhaud's neo-classical orchestral suite, Protée, Saint-Saëns said, “fortunately, there are still lunatic asylums in France.”

While this did little to endear The Grand Old Man to the young Turks of French music, he was still highly acclaimed as both composer and pianist among the general public, and frequently toured Europe and Northern Africa (which he loved: he would die there while wintering in Algiers). In 1906 and 1909, he successfully toured the United States, returning in 1915 (pushing 80) for San Francisco's “Panama-Pacific Exposition.” For this, he composed a well-received but quickly forgotten extravaganza for large orchestra combined with John Philip Sousa's band and a 117-rank pipe organ called Hail, California!

Saint-Saëns however will be forever remembered by music-lovers for beautiful melodies like “The Swan,” or the grander moments of his Symphony No. 3, the “Organ” Symphony, or delightful concert pieces like the Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso and of course, at this time of year, his Danse macabre, among numerous other tried-and-true war-horses. And it was perhaps that tramp of the war-horses heard behind them – like Brahms and the footsteps of a giant like Beethoven – that led them to evaluate him as “a consummate master of composition,” with a profound knowledge “of the secrets and resources of the art” but who never really rose above the level of a fine craftsman.

To be honest, though he began as a “modernist” in his early days, he was never one to “keep up with the times” as many other composers did during their careers, especially given Saint-Saëns started composing when he was 3 and wrote his last works shortly before he died at 86! For all his being derided as a conservative by his critics, Saint-Saëns wrote in his memoirs:

“Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotions, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.”

As Grove's Dictionary notes, following this quote, “it was perhaps his aesthetic rather than his music which most influenced his pupil, Gabriel Fauré, and later, Ravel.”

In that sense, Maurice Ravel (represented by two works later on this program) could make these two contradictory comments about Saint-Saëns around the same time:

When Francis Poulenc was an 18-year-old would-be composer looking for a teacher (this would've been 1917) and a pianist-friend had recommended he talk to Ravel (working on his Tombeau de Couperin around the time), Ravel thought the young man needed to learn the craft of composition, the ins-and-outs of what makes harmony work, for instance, or how to employ the old rules of counterpoint to your own style – in fact, Ravel's own teacher, Gabriel Fauré, had said much the same thing to him at the start of his studies – but Poulenc was dumbfounded when Ravel suggested he should study the music of Camille Saint-Saëns.

Now, from what I've found on-line, already suspect (and even a lot of the anecdotes in otherwise reliable biographies can be, as well: history is such a fickle creature...), I'm not sure he didn't mean to “examine his music, study his scores, look at how he handles his harmony, his counterpoint” and so on, rather than “go and ask to study with the man” which I don't think would've seriously happened, anyway. But the regard was there, whether he actually called Saint-Saëns a genius or not. It is important for young composers to learn craft: what they do with that craft is what makes them composers.

But Ravel is also supposed to have said, in response to some new piece of Saint-Saëns' just premiered, “If he'd been making shell-cases during the war, it might have been better for music.”

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| The curtain goes up on The Rite of Spring |

Imagine you've just created your third ballet and suddenly found yourself famous for having created one of the most startling works in the world of Classical Music, credited with the unlocking the floodgates to the New Music of the 20th Century.

It's Paris, May 29th, 1913, and your ballet is called Le Sacre du printemps or, as it's usually translated into English, The Rite of Spring (the original Russian title is more literally Sacred Spring). It caused one of the great riots in Classical Music, if you can imagine that. Boos and catcalls that made it difficult to hear the music eventually crescendoed, as the composer described it, into “a terrible uproar” that was so loud, the dancers could no longer hear the orchestra or the beleaguered choreographer shouting out the numbers to help them keep in time with the complex rhythms and dance patterns. (It's interesting to note the New York Times, reporting on it several days later, headlined the review “Parisians hiss new ballet” [indeed!], that the house manager “has to turn up lights... to stop hostile demonstrations as dance goes on”... but deemed the work “a failure”.)

I've already mentioned the famous legend of Camille Saint-Saëns, 78 at the time, stomping up the aisle shortly after the music started (see above) which no doubt gave everybody the go-ahead to express their own opinions.

Now, most ballet audiences were there to be entertained, especially with beautiful young dancers in diaphanous costumes dancing gracefully to pleasant music that told a story, usually romantic and most likely sad if not tragic. The Rite of Spring was none of these things. (Well, tragic, maybe, if you were the Chosen One...)

Books have been written about the importance of this single piece of music, its “liberation of rhythm” and changing the focus away from the beautiful melodies of the Romantic Age and those complex harmonies that had evolved through Beethoven to Wagner; not to mention about its premiere – including one by our own Dr. Truman Bullard. I was going to include a lot more background about this musical episode pitting the Old World of Saint-Saëns against the New World of Stravinsky, but in the interest of not bogging the reader down at this point, I'll get on to the Stravinsky piece that's actually on the program!

So, if you were Stravinsky and you've taken this new musical style of yours about as far as it can go where do you go from here?

Though a non-musical factor, let's consider the environment he lived in: Paris was a place where someone could manage to pull off a Rite of Spring, but now the World itself was in chaos: World War I had begun shortly after The Rite was premiered and in 1917, Stravinsky's native Russia ceased to exist. There were personal losses and he found himself in financial difficulties. With everything else, he found himself a composer without a country. Eventually, he spent the war years mostly in Switzerland (he had written much of Le sacre there while on holiday).

Economically at least, this was not the time to be writing lavish works for large orchestras and theaters. Instead, he wrote a number of songs, small chamber works, and clearly started redirecting the focus of his musical language.

After the vast scores of the Late 19th Century, a new, more “slimmed-down” approach to music began to focus more on leaner textures, clearer structures with a simpler harmonic language of a previous age with an increase of interest in “ancient music” like the symphonies of Mozart and Haydn and the baroque works of the early18th Century. Despite the reliance of a number of influences from the Baroque, this particular style of music is known as “Neo-Classical.” But that refers to the classical concepts of its texture and clarity of form rather than its stylistic “surface language.”

Aspects of music, incidentally, championed by the likes of Camille Saint-Saëns.

And that is what we hear in this new work Igor Stravinsky began in 1917, a work intended for a small ensemble that could be taken around and performed in smaller venues, not the great opera houses and concert halls of the world's major cities. It was, in any number of ways, more economical.

L'Histoire du soldat or “The Soldier's Tale” is a theatrical work meant to be played, spoken, and danced. The story is based on a Russian folk-tale , a Faustian parable adapted by Swiss writer C. F. Ramuz, writing in French, where basically Boy (in this case a young soldier on leave) plays fiddle, Boy loses fiddle (to the Devil in return for untold wealth), Boy gets fiddle back (in a card game with said Devil), then plays an ailing Princess back to health (a series of dances including a tango and some rag-time); Boy marries Princess, Devil attacks Princess, Boy subdues Devil with his fiddle (in the Devil's Dance), but then is cursed that if he ever crosses beyond the border of the Princess' realm, Boy will lose everything – which, of course, he does. And so, the Devil wins after all.

The instrumental ensemble, unlike the vast orchestra of Le sacre, consists of only seven players: violin and double bass, clarinet and bassoon, cornet (or trumpet) and trombone – in other words, balanced pairs of upper and lower register strings, winds, and brass – and an array of percussion instruments played by one musician – a snare drum, two side drums (large & small) without snares, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle. There are three actors taking the roles of the Narrator, the Soldier and the Devil; the role of the Princess is played by a dancer (additional dancers are optional).

But that's the original piece. You can watch a full, staged production of it here (in English) or follow the score in this full performance (with spoken text in French) where you can see how many of these rhythmic cells overlap between what you hear and what is written.

Like many operas or sets of incidental music, composers compiled collections of highlights into a suite, and that's exactly what Stravinsky did with this version for piano, violin, and clarinet. Not the whole piece, just some of the best bits, and instead of being a real piano part, the pianist substitutes for many of the missing instruments, even the percussionist.

It seems the financial backing for this project – think of it as L'Histoire, LLC – came from Swiss financier Werner Reinhart who was a major philanthropist, supporting several composers, painters, and poets in those years around and after the war; he was also an amateur clarinetist. After bankrolling Stravinsky's premiere, he gave additional money to back the tour of subsequent performances, and out of gratitude Stravinsky arranged this suite with the clarinet as a nod to Reinhart.

Here's the Suite – which consists of the opening “Soldier's March,” an introduction to the Soldier's fiddle, “Un petit concert” after the Soldier defeats the Devil and wins back his fiddle, then the set of three dances (Tango, Valse, and Rag) in which the Princess is cured of her curious malady, and, to conclude, “The Devil's Dance” in which the Soldier once again defeats the Devil.

The Ducasse Trio performs the Suite from L'Histoire du Soldat, “The Soldier's Tale,” in this performance recorded live in Manchester UK in 2016:

There are many fingerprints of this new “Neo-Classical” Style in Stravinsky's music, compared to what we'd heard a few years earlier in The Rite of Spring. While the bass (or in this case, the pianist's left hand) plays a constant “left-right/left-right” beat one could easily march to, everything above it is in the constantly fluctuating meters that were a hallmark of The Rite, a bane to many foot-tappers' existence. Instead of the rich layers of sound in Petrushka or Le sacre, what we hear here is more often something melodic (not necessarily a tune) superimposed over a simple, often repetitive accompaniment (not unlike an old-fashioned Mozartean Alberti Bass, so simplistic even a child could play it).

Stravinsky also has started to borrow material from the past. From Petrushka with its folk-song quotations, this quickly evolved into folk-like motives or themes in Le sacre with its original but derivative ideas. There are chorale tunes in L'Histoire meant to signify religious piety to remind us of Martin Luther or Bach, and of course those three dances evoke a sultry Parisian night-life. Interestingly, Stravinsky never heard ragtime live – he only saw it in printed sheet music and admitted his rag is more like a portrait of ragtime, much the way Chopin's waltzes are “portraits of the waltz” rather than waltzes intended for actual dancing.

It's interesting to look back on what Saint-Saëns thought was important in music – clarity of texture, harmony and form – things he imparted to his students and who, like Fauré, imparted to theirs (most especially Ravel). While Stravinsky “experimented” with Old Music after The Rite of Spring, a style that would be perfected by French composers like Milhaud and later Poulenc in Les six, or with Respighi in Italy in the 1920s that would become the “Neo-Classical” style (what critics called “The Grave-Robber School of Music”), Saint-Saëns had already been doing that: listen to the film score he wrote in 1908 for The Assassination of the Duc de Guise or movements of earlier works like the 1863 Suite, evoking the 16th Century dance suites of Rameau and Lully, though more rigidly and with less imagination than Debussy or Ravel would do in their own style at the turn of the century.

So, the Stravinsky that metaphorically met Saint-Saëns at The Riot of Spring in 1913 was not the same Stravinsky you're hearing in The Soldier's Tale four years later. In these age-old aesthetic skirmishes between Conservative and Contemporary, perhaps, like the Devil in the story, Saint-Saëns won after all.

– Dick Strawser

No comments:

Post a Comment