This Wednesday evening marks the third and last concert of Market Square Concerts' Summermusic 2023, a performance by the Escher Quartet, returning to Temple Ohev Sholom on Front Street below Seneca Street. The program includes a quartet Haydn wrote in 1793, the 4th Quartet Bela Bartók wrote in 1928, and one of two quartets Franz Schubert wrote in March of 1824, the one known as the "Death and the Maiden" Quartet. The concert begins at 7:30 and tickets will be available at the door.

|

| The Escher Quartet (outstanding in their field) |

The six quartets Franz Josef Haydn published in 1793 – two sets of three: Op. 71 and Op.74 – are often collectively referred to as the “Apponyi” Quartets for the same reason Beethoven's Op.59 Quartets are the “Razumovsky” Quartets: Haydn dedicated them to a cousin of his patron, Prince Nicholas Esterházy, named Count Anton Georg Apponyi, a member of an old and powerful aristocratic Hungarian family. A collector of paintings and an avid musical amateur, known as “an excellent violinist,” he would later become a founding member and then president of the famous Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, the legendary Society of the Friends of Music, in Vienna. There are some references that in 1795 he suggested Haydn's young student Beethoven ought to try his hand at a quartet.

|

| Haydn in London, 1791 |

Mozart died while Haydn was in London for his first stay. Then, after he received a comparatively cool reception in Vienna on his return, Haydn decided to accept an invitation for a second tour in 1794. This time, during the summer of 1793, he wrote six new quartets specifically for a projected series of London concerts and Count Apponyi was willing to pay 100 ducats (whatever that might be worth in today's dollars) for the dedication, the 18th Century's equivalent of “naming rights.” In previous cases, such patronage involved “performing rights,” a period of ownership that would preclude other music-loving aristocrats (and wealthy merchants, too, like Johann Tost, who'd once been a violinist in Esterházy's orchestra) from being able to have them played at their musicales.

So, with little fanfare, then, Haydn ended up creating the first string quartets written for the paying public, not a wealthy patron. Whatever sense of freedom this may have given Haydn, these quartets exhibited a subtly new approach: biographer Rosemary Hughes wrote, “It is as if Haydn were pushing open a door through which Beethoven was to pass.” Seven years later, Beethoven would present his own set of six quartets, his Op.18. And more than just a new century had begun.

The quartet on the Escher's program, the D Major Quartet, Op.71 No. 2, opens with a brief, four-measure slow introduction setting up the main Allegro. Rather than being a simple melody-with-accompaniment, the accompaniment begins to branch out with a more defined independence with the occasional slip onto an unexpected chord or a switch to the darker minor mode (Haydn was always good for something unexpected, but here they're more subtle: we, used to Beethoven and Bartók, might not even notice them, today). The frequent use of the octave leaps throughout the Allegro might bring to mind the “motivic saturation” of Beethoven's 1st Quartet's opening movement.

The slow movement, one of Haydn's great Adagios, unfolds like a seamless meditation. Presumably in sonata form, Haydn again creates the unexpected by smoothing over the usual formal signposts until, really, while the structure is there, it needn't be so obvious. The third movement, more earthy than elegant as expected, is certainly well on its way to becoming the scherzo Beethoven will later be given credit for. And then its middle section, the standard trio, certainly a contrast, seems to lack a theme at all. (By the way, notice the octave leaps, filled in here, as if left over from the first movement.)

The last movement begins as a gentle Allegretto in the manner of a folk-like dance – not an all-out Hungarian dance, in honor of Count Apponyi – a simple tune that would be out of place in a first movement but fine in a light-hearted finale. It becomes increasingly more active, more dramatic, then breaks out into a sprint for the finish, a brilliant conclusion. An old joke about programming a concert to end with a flourish to spark the applause: “play it faster and louder!” Even though Haydn has only four instruments here, he's already managed to figure out how to get a hearty response from enthusiastic fans.

Performed by the Maxwell Quartet from the UK.* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

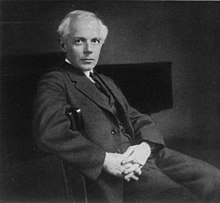

| Bela Bartók in 1927 |

It's not unusual for a string quartet to program three different quartets from three different historical periods: Classical 18th Century, Romantic 19th Century, and “Modern” 20th Century (what will we call 21st Century works in the grander scheme of things?). In this case, following them chronologically, we have Haydn from 1793; Schubert, 31 years later but a whole world away, in 1824; and Bartók over a century later in 1928 on the verge of a world depression and halfway between one World War and the next.

To many listeners, Bartók still strikes us as “contemporary” despite the 95-year age difference. At his best, he is not exactly easy listening (then, neither is Schubert's Death & the Maiden Quartet by 1820s standards, much less Beethoven's Late Quartets of the same decade). As often happens, people put off by the unfamiliar tend to focus on what's different; if we listen to Bartók and think about what's similar to what Beethoven and maybe even Haydn were doing, it might be easier to become more comfortable with his musical language.

Bartók initially grew out of the “enforced” status quo of the Vienna of Brahms and Richard Strauss. Hungary was long part of the Austrian Empire even if, since the mid-19th Century, it officially became the Dual Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – and Bartók was adamantly Hungarian as a hot-headed youth. His first major work, written in 1903, was a vast tone poem after Richard Strauss' Ein Heldenleben, inspired by Laszlo Kossuth, the leader of Hungary's 1848 Revolution. He depicted the Austrians with a satirical parody of their national anthem; the crushing defeat of the Hungarians became a funeral march with echoes of Franz Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. Needless to say, a success in Budapest, it didn't go over too well in Vienna.

If hearing (and meeting) Strauss in Budapest in 1902 was a life-changing event, so was the simple moment in time when, walking through a hotel on vacation, he overheard a nanny, originally (like him) from the Transylvanian region that was then part of Hungary, singing a lullaby that was an authentic Hungarian folk-song, the first real folk-song he'd heard. Up until then, “Hungarian folk music” meant the dance-band music of the gypsies. Brahms would haunt Viennese taverns to hear the gypsies play just as many Americans would hang out at New York speak-easies to listen to jazz. Those tunes Liszt, a Hungarian-born cosmopolitan who lived in Germany, in Paris, in Rome, would quote in his famous Hungarian Rhapsodies were actually the equivalent of “urban pop” music, not the Hungarian folk at all. This was about to change.

With his friend, fellow student Zoltan Kodály, Bartók began a study of this authentic folk music and started quoting them directly into short piano pieces like transcriptions, or using them in his 1st String Quartet completed in 1909. His love of folk music took him on many trips around the Balkans, eventually even to Turkey and North Africa. He (quite literally) wrote the book on Serbo-Croatian folksongs as a result of this life-long research, or at least Part One of it: it was completed posthumously and published in 1951 by his colleague, Albert Lord, at Columbia University where Bartók had been a research fellow after settling in New York at the start of World War II.

This folk music he heard and recorded was not performed by trained musicians but by the people he met in the villages and across the countryside of Hungary. With its particular sense of accent, rhythms, and vocal contours, this music had begun to permeate Bartók's music early in his career and soon he'd gone from quoting actual songs to creating original melodies “in their style.” By the 1920s, he began calling this “imaginary folksong.”

A series of his “mature works” began in the mid-1920s with the 3rd and 4th String Quartets in 1927-1928. To us, they may sound nothing like folk-music, but many of the rhythmic turns, the gestures, the melodic shapes and their narrow spans are all part of this “primitive” style rather than the niceties of a Schubert song or a Beethoven symphony.

Thinking in terms of “motives” rather than tunes, and “gestures” rather than melodic phrases, listen to how many of these take on specific characteristics as the work unfolds, particularly through the opening movement. Complete with supporting sustained chords like a drone, there's an all-out “melody” for the cello in the middle movement, a highly ornamented slow-moving line (in many folk musics, intonation is not based on the Western tempered scale: perhaps Bartók's use of these tight half-step intervals and fluctuating ornaments reflect what more timid American ears might consider “singing out of tune” or using microtonal inflections?)

Unlike the 3rd Quartet which is basically a single condensed movement, the 4th and 5th Quartets are five movement “arch forms,” with two shorter movements on either side of a central movement (the keystone of the arch), then the two outer movements often connected by common motives or rhythms. In the 4th, the keystone is this “night music” with sustained, almost static chords underneath a winding, undulating cello melody, full of surprising shimmers that bring to mind that once, as a student, Bartók was fascinated with his discovery of Debussy's impressionism.

Keeping with the idea of the arch, the 2nd Movement and the 4th reflect one another's hurried, almost frantic mood and their folk-like motives, even if the sound is markedly different. In the 2nd, it's muted almost like a will-o-the-whisp that suddenly erupts in terror, its icy glissandos like spirits in the air. (This movement is clearly inspired by the misterioso from Alban Berg's Lyric Suite of 1926 which Bartók heard in 1927, the year before he composed his 4th Quartet.)

It is not difficult to imagine some of the sounds Bartók asks for from his string players are not something that will sound effective when played “nicely,” especially the pizzicato or plucked passages in the wild 4th Movement, especially the “snap pizz” which rebounds off the fingerboard and became such a trait of his it is still called “the Bartók Pizz.” Not to mention some of the glassy – eerie – sounds in the other movements created by playing near the bridge of the instrument. And sometimes the transition from one “sound” to another can be so startling, some might wonder if they're listening to stringed instruments at all.

Here's a recording by the Keller Quartet with the score: even if you can't read music, you can see the shapes of the different lines moving sometimes together, sometimes in contrary motion, sometimes a repeated pounding accompaniment under a short repeated gesture in the upper parts (or vice versa). It's a different world, Bartók's, and even if you don't understand the language, like listening to a story teller who knows how to use his voice to create an effect where words might fail, you'll still get what's happening.

(A footnote: I remember listening to a rocking new recording of Bartók's 4th Quartet with members of the faculty string quartet where I was teaching back in the 1970s, and after this last movement, the first violinist turned to me and said very matter-of-factly, "So I imagine to a Hungarian that would be real down-home music.")

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| Schubert in 1825; watercolor by a friend |

|

| 1st page of the original MS of Schubert's Quartet, "Death & the Maiden" |

If you're not familiar with the song itself, it's interesting to compare the “quartet version” (beginning at 11:37 in the first video) to the original, the song D.531 composed in February, 1817 (Schubert had just turned 20). While he skips the opening vocal lines, the plea of the young maiden faced with the impending arrival of Death, he's not using the “melody” as we might think it, such as it is, what the singer's singing, Death's reply to comfort the young girl: it's the piano accompaniment, with its simple harmonies.

“Give me your hand,” Death sings, “you beautiful and tender form! / I am a friend, and come not to punish. / Be of good cheer! I am not fierce, / Softly shall you sleep in my arms!”

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

“It sometimes seems to me as if I did not belong to this world at all.”

It's a famous Schubert quote. Lucy Miller Murray opens her wonderful set of program notes about this quartet with it, and while I've found mentions of it in several on-line essays, I can find no direct reference to when it was written or to whom it was written (in a letter or in his diary?).

| |

| Kupelweiser's 1818 watercolor of himself (on a "dandy horse") and Schubert with a kaleidescope |

This is usually (and frequently) quoted as proof Schubert was depressed, an easy word to banter around in hindsight from a time when many people use the word as a synonym for “sad.” Certainly, after the horrible year he'd had before this, he should be allowed to feel a bit down, to understate it: after all, in 1823, he was ill much of the year – the first symptoms of syphilis (which would eventually cause his death five years later) had just appeared; he had been hospitalized in May – and he was, as usual, having money problems, especially after a disastrous deal with the publisher Diabelli. Plus his latest attempt at an opera was another failure (did you know he started over 20 operas, finished only 11 of them, none of them staged in his lifetime? Who wouldn't find that depressing...). He wrote Fierrabras (to a horrible libretto by Kupelweiser's brother) between the end of May and the start of October, 1823, but due to the failure of a new opera by Weber and the unstoppable rage for All Things Rossini, plans to stage his new work were shelved, then canceled. Not only had he spent four months writing it, he never even got paid for his commission! At the end of December, his incidental music for a “magic play” called Rosamunda, Princess of Cyprus was another unmitigated disaster, again mostly because of the ridiculousness of the play. Small wonder he put operas aside (for a while) to concentrate instead on instrumental works.

What is often overlooked, in that depressing quote from his letter to Kupelweiser, is that he continues talking about just that thing, how he was now finished two string quartets, an octet, “and I want to write another quartet; in fact that is how I want to work my way toward composing a grand symphony.” Hardly the words of a young man thinking his life was no longer worth living!

He had taken a fragment of music from that Rosamunda play and used it as the 2nd Movement for the first of these two string quartets, the one in A Minor listed in Otto Deustch's catalogue as D.804. It was even performed in public by no less than Ignaz Shuppanzigh's quartet (associated with Beethoven's quartets and formerly court violinist for Count Razumovsky), on March 14th, 1824; and even more importantly, published that fall. (Remember, his letter to Kupelweiser was dated March 31st...)

He almost immediately began another quartet, this one in D Minor, D.810, and while we're not sure when it was finished – the second half of the quartet's original manuscript is still missing – it was performed in private on February 1st, 1826. Did it take that long to complete, or did he put it aside, as he had a habit of doing? The “Unfinished” Symphony suffered a similar fate: stumped for a 3rd and 4th movement to stand up to the first two, he left it as it was, incomplete (perhaps, incompletable); and friends who'd been given the score didn't know what to do with it because, after all, it wasn't finished... so they just stored it in a box in their closet until 1860.

There are some twenty or so string quartets, complete or incomplete, in Schubert's output but most of these were “household quartets” (usually dismissed as juvenalia) written for his family's musicales when he was living at home: his brother Ferdinand was a respectable violinist, brother Ignaz not so much, and their father “played the cello,” so by default Franz, an adequate violinist, played the viola (then often looked upon as the “third violin,” where people who couldn't cut second violin parts were sent).

But by late-1820, Schubert – now 23 years old – began to write more “serious” quartets. While there exists 41 measures of a slow movement, all we have of this first new work is known as the Quartettsatz, D.703, and it's from here we can talk about Schubert's Mature Quartets but alas, he completed only three of these: the Rosamunda, the D Minor known as Death and the Maiden, and the last one in G Major D.887 of 1826, the three he mentioned in Kupelweiser's letter.

Yes, Schubert died in 1828 at

the age of 31, but keep in mind he also wrote, counting the

individual little piano pieces grouped together in some of his dance

collections, some 1500 compositions – the Deutsch catalogue numbers

his last completed work, the song The Shepherd on the Rock,

as D.965.

Imagine, as you listen to the concert, this string quartet is the music of a man recently turned 27 who had his whole life ahead of him. Then, insert the latest edition of the game, “What if...?”, here.

Dick Strawser