|

| The Schumanns, 1846 |

So now it's time to meet the Schumanns.

In 1828, a teenager named Robert Schumann arrived in Leipzig to study piano with one of the more acclaimed teachers of the day, Friedrich Wieck. He was, according to his family, supposed to study law, but he had already dropped out of school, traveled to Munich (where he met Heinrich Heine) and decided he wanted to write novels or compose music (or both). Wieck turned out to be a difficult master – Schumann had already given up law after a brief attempt to focus on “something practical” – but he also had a pretty and quite talented daughter named Clara who, at 14, had already begun work on writing her own piano concerto. Young Schumann volunteered to help her with the orchestration (not the kind of “pick-up line” most guys can get away with...).

It's a long story. Friedrich was not keen on losing his daughter – more importantly, losing control of his daughter and her future income. Since 1837, the two young lovers considered themselves engaged, but her father, rather nasty piece-of-work that he was, put every obstacle in their path he could manage. In turn, Robert and Clara sued Wieck in court, the judge sided with Schumann, but Wieck counter-sued that Schumann would be an unfit husband (he had, after all, no career and would be unable to perform as a pianist due to a hand injury) because he was “a habitual drunkard.” When proof of this was not forthcoming, the case was dismissed, and the wedding finally took place in a small church near Leipzig on September 12th, 1840, the day before she turned 21.

|

| Clara, Summer, 1840 |

Heine's poem, published in 1826 as part of a collection called Das Heimkehr (The Homecoming), describes a young man who, staring at his beloved's portrait, imagines she has smiled at him; but with a tear, he realizes, alas, he has lost her.

Perhaps an odd choice of text for a Christmas present – though it might certainly reflect the long period of anxiety prior to their wedding – but several other composers have set Heine's poem as well, including Schubert (as “Ihr Bild,” one of his final songs, in Schwanengesang, written in 1828), Grieg, Hugo Wolf, and Amy Beach, among some 92 others mentioned in one on-line song archive's “not exhaustive” list!

As their struggles to get married dragged on through 1840, Schumann, who'd composed mostly only solo piano pieces before, suddenly turned to writing songs.

Among the 138 or so songs he composed that year, 20 songs were written in the last week of May, including Dichterliebe (Poet's Loves), and in two days in July, Frauenliebe und -leben (Women's Loves and Lives). But a month after the wedding, Schumann began something new, something Clara had always been kind of badgering him about: he wouldn't be a serious composer unless he composed some symphonies (because that's what most composers did in those days). In October, 1840, he began sketches for what would become his 1st Symphony, the famous “Spring” Symphony, eventually composed over a period of four days in January (hardly spring-like weather, that) and orchestrated by the end of February, 1841.

A year before the wedding had taken place, Wieck had left Leipzig – presumably to get away from so many of Schumann's friends – and re-settled in Dresden, not all that far away. So the Schumanns chose to base themselves in Leipzig which, one of the leading musical centers of Europe, had a very fine orchestra led by Felix Mendelssohn who'd taken on the conductorship in 1835, sharing his time there with a busy touring schedule and official duties in Berlin as court composer for Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV which included writing incidental music for Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1844.

|

| Schumann in 1839 |

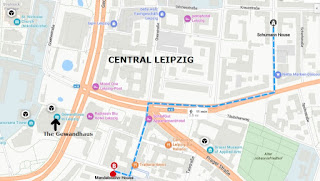

At the time, the Schumanns, now newlyweds, lived in a 2nd floor apartment of an imposing apartment block (see photo and map of Leipzig in the previous post) where Schumann composed his first two symphonies and a “Fantasy for Piano & Orchestra” which a few years later became the first movement of his famous Piano Concerto in A Minor – all in 1841. And then three string quartets, the Piano Quintet and Piano Quartet all during the summer and fall of 1842. It was here the Schumanns received guests like Mendelssohn, Berlioz (who visited twice in 1843) and Wagner who'd moved to nearby Dresden in 1843 with the premiere of his first lasting success, The Flying Dutchman.

|

| Clara w/Marie, 1844 |

After several weeks on the road, Schumann became uncomfortable not only with the constant traveling but also realizing he was essentially regarded as “Mr. Clara Schumann.” He returned to Leipzig as she took off for Copenhagen – he had responsibilities with the magazine he'd founded, Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1834 – but was instead challenged by bouts of melancholy, drowning himself “in beer and champagne,” and unable to compose. He filled his time with the equivalent of “creative crossword puzzles,” filling notebooks with technical exercises in counterpoint and fugue (the composer's equivalent, at the time, of a pianist's scales and arpeggios). Before they'd left on the tour, he'd been “visited by quartet-ish thoughts” and so began studying string quartets by first Mozart and Haydn, then Beethoven. Meanwhile, Papa Wieck was spreading rumors that the loving couple had already broken up, their marriage on the rocks.

When she returned home in late-April – talk of an American tour was put on hold – Clara joined in with Robert's studies, and then on June 2nd, he began what he called “quartet essays.” On June 4th, he began work on an A Minor Quartet and even before it was completed, he'd begun sketch a new quartet on the 11th, completing the A Minor on the 22nd. After finishing the 2nd Quartet – and becoming involved in a “a libelous onslaught” with a long-time rival which earned him no less than 6 days in jail!!! – he sketched out a third quartet between July 8th and the 22nd. After a short August vacation (which his nerves no doubt needed) and after hearing a run-through of all three quartets on September 8th, he then completed a new Piano Quintet by the end of the month, and a new Piano Quartet, begun after “constant fearful sleepless nights,” completed in November. There was also a piano trio completed in December which, along with another work, he was dissatisfied with and set aside to rework them later.

The first of Robert's string quartets shows the fruits of his studies, both of Bach's counterpoint and of the Classical Quartets of his predecessors. It opens with a slow, mysterious evocation of Beethoven's late style with a good bit of imitation between the different instruments (a.k.a. counterpoint), but otherwise the first movement is the expected traditional “sonata form” except for one peculiar digression: it's in the wrong key. (This has always puzzled me: in a realm that was careful to play by the rules, it seems an odd slip to make; but then, what does it matter when it's so pleasant to listen to and otherwise does everything required of it?)

The second movement is a scherzo (usually reserved for third place in the overall scheme of things) and in this case, clearly a bow to the elfin style of Mendelssohn's fleet-footed scherzos like those in the Octet or the Overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream. In this case, I would say it's a very conscious hommage given Schumann ended up dedicating all three quartets to his friend and champion.

No one can fault Schumann's gift for melody. Perhaps it was having written all those songs two years back. Regardless, whether a skill or a naturally honed talent, this third movement is only the first of a series of “romances” to be written that year, climaxing in the gorgeous slow movements of the Piano Quintet and the Piano Quartet of only a few months later.

The last movement, then, opens in a burst of drama quickly scurrying off with the same kind of kinetic energy that propels the finale of Mendelssohn's Octet, an energy that isn't even dampened by the rustic stamping in the cello's drone. Surprisingly, this turns out to be an even more standard “sonata form” movement than the first movement, except this time, Schumann introduces something new for the “coda” (literally, “tail”) which wraps it up: while the country dance is never far away, suddenly we have a passage reminiscent – drone and all – of a musette or hurdy-gurdy (in this instance played without vibrato to heighten the impression). An even odder passage is a simple harmonic progression, all in whole notes, that brings the opening energy down to a sense of suspended animation, before returning to the main motive, bringing everything to an affirmative and certainly energetic conclusion.

= = = = = = =

(you'll need to click on the square-ish icon in the lower right corner to view it full-screen in order to see the score)

(though uncredited, a comment indicates it's performed by the Cherubini Quartet)

(my apologies if you've gotten hit by the gauntlet of YouTube ads that pop up in the most annoying places, sometimes in the middle of a phrase. Reminds me of that childhood "interrupting cow" knock-knock joke...)

= = = = = = =

Aside from the obvious references, stylistically, to Beethoven and Mendelssohn, as well as the legacy of his recent studies of Mozart and Haydn quartets, consciously or not, the forensic musicologist in me also hears certain turns of phrase that distinctly belong to one of the most frequently performed composers of the day, Ludwig Spohr, though now largely forgotten and rarely performed. Spohr wrote over 30 quartets and you can, if interested, check them out with a search on YouTube.

It's also interesting to immediately go and listen to all three quartets in quick succession – binge-listening, for lack of a better name – to get a feel for Schumann's writing all of them in the space of only six weeks. Here's the 2nd String Quartet in F Major (a friend of mine, hearing it for the first time, said Schumann was “clearly ripping off Brahms,” except Schumann wouldn't meet Brahms for another 8 years and Brahms wouldn't be the composer we'd know, worth ripping off, for a few more years after that); and the 3rd Quartet in A Major.)

The progress he'd made in his composing in general, from a technical standpoint, but his string quartet writing specifically is amazing. Somewhere, with the finale of the 1st – which presumably he hadn't written yet when he began the 2nd Quartet – the music begins to sound more effortless, more “sincere” for lack of a better subjective term. Most of all, the counterpoint sounds less self-conscious. The opening of the 2nd has an ease about it: perhaps, having broken the ice with this first “essay in quartet-writing,” he'd overcome whatever fear he'd felt, approaching his first piece of chamber music and discovered he really could do this. There's a self-assuredness with the 3rd Quartet that leads directly to the two chamber pieces with piano – he could now write something specifically involving his wife in the performance.

And is it too much to point out, recalling that summer vacation taken before he embarked on the Piano Quintet and the Piano Quartet, that nine months later, their second daughter Elise was born?

But then, after these heady months of intense creativity, suddenly he'd become exhausted by the effort; that and his creativity seemed to lose some of its steam as the months of activity wore on. He became ill and completely unable to work.

This set up a pattern that would eventually grow into one of the saddest stories of “tortured creative genius.” It has been called “manic depression” but more recently became classified as “bipolar disorder,” where periods of creative inactivity were followed by bouts of incredible and often “violent” activity – seriously, writing the rough draft of his 1st Symphony in four days?? – which, then leaving him exhausted, led to another extended period of depressive inactivity. He often found himself unable to engage in conversation, often sitting in a room, silent and withdrawn.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

In 1843, the year after Schumann's explosion of chamber music, Felix Mendelssohn began planning a new Conservatory for Leipzig, and Robert Schumann became involved in many of the preliminary discussions. However, it was Mendelssohn's energy and organizational skills – the extrovert to Schumann's introvert, perhaps – that established the school. Schumann was initially engaged to teach composition as well as piano and score-reading; Clara, despite being pregnant with their second child, was still busy with concert tours, and would become involved later, teaching when she could maintain a “more regular schedule.”

Unfortunately, Robert, given Clara's “distance” (both emotionally as well as physically), was often in a “melancholy state” as he described it, finding it difficult to speak, and students complained he would sit through a lesson or rehearsal rarely saying a word. In December, 1843, however, his recently completed oratorio, Paradise and the Peri, was ready for its premiere and he reluctantly agreed to conduct it, something he'd never done before. Remarkably, with Clara as the rehearsal pianist, he got through it satisfactorily enough though he was not entirely an effective rehearsal technician.

|

| Schumann, 1844 |

In June, Robert resigned from the editorship of the Neue Zeitschrift and in August, Clara officially joined the faculty at Mendelssohn's conservatory. But soon Robert had a complete mental breakdown, so weak he could barely walk across the room. He now had pains, trembling and weeping, and was often unable to sleep. This time, pregnant with their third child, Clara canceled a concert tour and stayed home. Visiting Dresden, only a few hours away by train, they eventually decided, rather suddenly, to leave Leipzig behind and in December, 1844, moved into a new apartment in the Saxon capital.

But that would begin another chapter.

The remainder of this post takes the story of the Mendelssohns and the Schumanns a bit beyond the biographical coincidence of this program's music. Consider it “extra-credit” (there will be no quiz following the concert, however). I've also written other posts about both Mendelssohns and Schumanns which you can read here: Mendelssohn's Sister and Her World and Mendelssohn's Life, Mendelssohn's Death (both from a project for high school students); The Extraordinary Life of Clara Schumann; and And Schumann at the Close.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Felix Mendelssohn was 38 years old when he died in 1847 – file under “Composers Who Died Young” (why does that sound like a “Jeopardy” topic?). We often think of Mozart, dying at 35, and Schubert, at 31, but we tend to overlook Mendelssohn wasn't that much older. In fact, his sister Fanny, four years his senior, was only 41 when she died following a stroke that occurred during a rehearsal of Felix's Walpurgisnacht cantata, planned for an upcoming family Sunday musicale (yes, the family still gave them and, yes, they were still attended by many friends and visitors, just like their parents had done decades earlier). Taking the news of Fanny's death hard, Felix was often ill and distraught, taken off to a spa in Switzerland to recuperate and grieve. He struggled to complete a string quartet, his sixth, in the dark key of F Minor which is often referred to as his “Requiem for Fanny.” Not much later, he too had a stroke and died only six months after Fanny.

|

| The Schumanns, 1850 |

|

| Clara in early-1854 |

After he was taken away that evening, Clara, already pregnant with their last child, a son who would be named Felix (in honor of their friend Mendelssohn), never saw her husband again until late-July of 1856, two days before he died at the asylum outside Bonn. He was 46. She was 38.

Meanwhile, now, Clara was forced to support herself and her children – and later, after the deaths of two of them, several grandchildren she now raised – returned to the concert stage, touring frequently until arthritis and neuralgia made it more difficult even to practice on a daily basis much less perform. Among her final performances was Robert's Piano Concerto in 1885 with her half-brother, Woldemar Bargiel, a composer and conductor – as the son of Clara's mother by her second husband, this makes one wonder if Friedrich Wieck could take, as he did, all the credit for creating the genius that was Clara! – and then, at her last concert, Brahms' Variations on a Theme of Haydn in 1891.

As a composer, it might be understandable, looking at the number of children Clara was raising and the husband she was looking after, not to mention her performing and teaching career – and don't forget, she had been unable to use the piano to write or practice while Robert was composing his own works – it's not surprising she'd never had the “serious time” required to become a composer on a regular basis. Her last works to be published were a set of variations on a theme by her husband and the three Romances for solo piano written for his birthday in 1853.

|

| Lenbach's portrait for her 60th Birthday |

Her husband also expressed concern about the effect on her composing output: “Clara has composed a series of small pieces, which show a musical and tender ingenuity such as she has never attained before. But to have children, and a husband who is always living in the realm of imagination, does not go together with composing. She cannot work at it regularly, and I am often disturbed to think how many profound ideas are lost because she cannot work them out.”

(Not, one could add in modern hindsight, that he ever seemed to offer some way to help her work this problem out...)

Clara Schumann died in Frankfurt in 1896 at the age of 76, following a stroke. Brahms, who'd received the telegram about her death too late, barely made it to the funeral in time, following problems with train schedules and mistaken directions, only meeting the procession on its way to the grave site. Brahms himself would die within a year at the age of 63.

Then finally, Clara was laid to rest beside her husband in a cemetery in Bonn.

- Dick Strawser