|

| Zemlinsky by Emil Orlik |

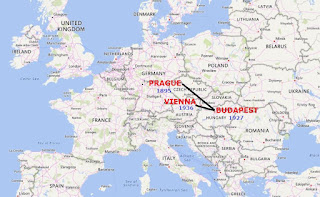

The music on this program originates in a fairly limited geographic area of Central Europe – from Prague to Budapest and back to Vienna – that would fit into an area roughly covering the distance from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia. The works were written within a span of 41 years. While the Bartók quartet may sound more “modern,” the Zemlinsky quartet is chronologically the most recent of the three, composed in 1936.

And going from Dvořák/Prague/1895 to Bartók/Budapest/1927 to Zemlinsky/Vienna/1936 also takes us from the more familiar to the most likely unknown.

Who is Alexander Zemlinsky (or as you might sometimes see him, Alexander von Zemlinsky)?

I admit I'm not that familiar with his music and though I've listened to a few recordings of his works, I don't recall ever hearing anything of his “live,” or (more damning) remembering anything beyond a general curiosity: the fact his music never grabbed me quite the way hearing Bartók's 3rd did when I was a student, reflects more on me than on Zemlinsky, but it's often the fate of composers who, thinking of the Olympics we've been experiencing the past two weeks, never made it onto the medals podium at the end...

Considering how little of Zemlinsky or his music is known, I decided to opt for a more complete life-long biography rather than just discussing the work-in-question. I apologize for the length (if I had more time, I would have written less).

Feel free to scroll down till you find the music videos if you don't have the time or inclination to read everything. But also remember, you can return to the post and read it after the concert. It is – trust me – an interesting story and worth the effort.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

One of the things that fascinates me about him is how a composer with the connections he had never attained a more enduring reputation? He had the backing of no less than Johannes Brahms at the start of his career; and it was a similar kind of mentoring that could've developed into the same kind of sponsorship Brahms gave Dvořák if only the Grand Old Man had lived longer. Along the way, he was championed by Gustav Mahler who conducted two of his operas in Vienna, the first when he was 29. With his friend, sometime student, and eventual brother-in-law, Arnold Schoenberg, he was regarded as a leading light in Vienna's “new music scene.” As a member of various musical organizations in a city full of such “clubs,” he was regarded as an influential musician, teacher, and composer in a city loaded with composers, most of whom are even more unknown than Zemlinsky (if we continue the Olympic analogy, ones who never made it to posterity's preliminary rounds).

Zemlinsky is, in a way, an ethnic miniature of the Austrian Empire, a polyglot political patchwork that imposed Germanic culture across most of Central and South-Eastern Europe from the 16th Century to the end of World War I. His paternal grandfather was of Polish Catholic descent who was born in a part of Hungary now in Slovakia who married an Austrian woman. His maternal grandfather was a Sephardic Jew from Sarajevo in the Balkans (previously part of the Ottoman [Turkish] Empire) who married a Bosnian Muslim woman. When Zemlinsky was born in Vienna in 1871, the entire family had been converted to the Jewish faith. For some reason, the composer's father had added the aristocratic “von” to his name, but as soon as Alexander was gaining recognition as a composer, he dropped the “von” which was, essentially, if not illegal, at least pretentious.

|

| Zemlinsky in 1898 |

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Most of what we know of Zemlinsky orbits around the peripheries of three people: Schoenberg, Mahler, and a composition student of his who would later become Mrs. Gustav Mahler (and would eventually marry the architect Walter Gropius and the writer Franz Werfel) – Alma Schindler.

In 1900, Gustav Mahler accepted Zemlinsky's new opera, a fairy-tale story called Es war einmal (the German equivalent of “Once upon a Time”). He was 29 and it seemed his whole future was quickly opening before him.

Shortly after the relatively successful premiere (the opera ran for a dozen performances, at least), Zemlinsky was having dinner at a friend's in late-February where he found himself chatting with a beautiful young lady who was studying composition but who had not yet seen Es war einmal though she was quite a fan of the conductor, Mahler. He suggested she should make an appointment to meet him, impressing her with his connection.

|

| Alma Schindler in 1900 |

Eventually, Zemlinsky became her composition teacher (it's quite possible he was more dazzled by her beauty than her musical talent) and wrote maddeningly passionate love-letters to her. As one source put it, “she tortured him for about a year” before finally breaking off their relationship on the advice of her family who's primary objection was he was Jewish as well as ugly. Alma's diaries are full of anti-Semitic comments, yet two of her three future husbands were Jewish – Mahler and Franz Werfel. In 1901, Alma Schindler began seeing Mahler and after a whirlwind courtship, they were married in 1902 – once Alma promised to give up composing (he insisted he wanted a wife, not a colleague).

More to the point of Zemlinsky's music, let's return to his friendship with Schoenberg. They'd met around 1895 (the year Dvořák composed his last quartet) when Zemlinsky founded an amateur orchestra in which one of the cellists was a self-taught would-be composer named Arnold Schoenberg. Zemlinsky, though only three years older, gave Schoenberg advice and general instruction about his compositional endeavors, and they became close friends. In 1898, Schoenberg converted to the Lutheran faith – he would later, in the face of the Nazi occupation of Austria, reconvert to his Jewish roots before fleeing to the United States – and in 1901 he married Zemlinsky's sister, Mathilde.

| |

| Gerstl's Group Portrait with the Schoenbergs |

[Gerstl's painting, by the way – see above – was done that summer and consists of three couples: Arnold and Mathilde Schoenberg (standing) with Alexander and Ida Zemlinsky (seated in front) with another couple that (not surprisingly) cannot be identified.]

Mathilde died in the fall of 1923 and the following summer, Schoenberg married the sister of a pupil of his, the violinist Rudolf Kolisch, who would found a quartet that would champion Schoenberg's music.

Now, I mention all of this because – regardless of the argument against the impact of biographical details on a composer's music – these events had a direct influence on Zemlinsky's music.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

But first, let's hear a little bit of what Zemlinsky sounded like before he wrote the quartet we'll hear on Sunday's program: the Escher Quartet has recorded all four of Zemlinsky's quartets, and here they play the opening movement of his 1st Quartet (listen to a few minutes of the opening if you don't have time for the whole thing):

The 1st Quartet was written during the time Brahms had arranged a monthly stipend for the 25-year-old composer so he could concentrate on writing, and after its premiere in 1896 (compare this “sound-world” to Dvořák's last quartet in the first post), Brahms told friends it was “bursting with talent,” though he objected to some of its “modernist” tendencies in an awkward private conversation with its young composer. Basically, he pulled out a score of a Mozart string quintet, pointed out a particular passage as “perfection” and said quite matter-of-factly, “that is the tradition handed down from Mozart – to me.”

Zemlinsky's 2nd Quartet was begun in 1913 in the years following the episode in which his sister had run off with the painter Gerstl, and reflects the emotional turmoil he felt and observed both his sister and her husband going through. This is far from an abstract work built on forms and harmonic formulas! Completed in 1915, the quartet was dedicated to Schoenberg.

It's a vast, dramatic expanse lasting some 40-45 minutes, full of musical cyphers where motives are associated with people or events and sometimes motives that act like “code” created from a person's name. He assigns one three-note motive, D-E-G, to “the self” (basically, himself) and by transposing it to A-B-D, adds an E to create “Mathilde,” keeping in mind B in German is represented by H (that's how you can spell B-A-C-H in musical pitches): so, we have mAtHilDE.

The quartet opens with “The Self” motive as if Zemlinsky is the observer, the teller-of-the-tale. One also hears a chord – a D Minor triad with an added G-sharp – which becomes a “code-sonority” for “Fate,” something Zemlinsky used frequently in many of his later works, as well.

In the intervening 17 years, Zemlinsky's style has gone from being heavily influenced by Brahms to absorbing the chromaticism of Wagner's Tristan. Keep in mind, Schoenberg wrote his Wagnerian Verklärte Nacht by 1900 and his atonal break-through piece, Pierrot Lunaire, in 1912. While Zemlinsky has gone much farther afield from Brahms' advice than the Grand Old Man could ever have imagined, he has never gone nearly as far as Schoenberg: despite the intensity of his chromatic harmony, this quartet is still distinctly tonal and reminds me more of Schoenberg's own 1st Quartet (also in D Minor) from 1905 (and also in one unbroken span of about 45 minutes).

|

| Zemlinsky & Schoenberg |

He also realized he had taken his style about as far as it could go and so he fell into a period of silence as he tried to figure out what he might write next, what he could do to find inspiration – not unusual for composers facing a “style change.”

|

| Zemlinsky with Cigar |

Then, later that same year, his sister Mathilde died. It was customary in the Jewish tradition for the surviving spouse to wait till the end of the official “year of mourning” before remarrying, but Zemlinsky was shocked when Schoenberg announced two months before the mourning period ended that he was marrying Gertrude Kolisch. Whether Zemlinsky saw this as a “substitution” for his sister or not, he clearly was very distressed by Schoenberg's decision. (Admittedly, this doesn't make a lot of sense to me since, by this time, neither was still active in the Jewish faith, and while Zemlinsky never considered himself religious, his widow told his biographer in the 1980s “My husband did not consider himself Jewish,” but that's another story.)

Around this time, Schoenberg had gathered his friends and students together to introduce his new ideas about “composing with twelve tones,” a systematic approach to organizing pitches in lieu of tonality – and for that matter, the arbitrariness of atonality – something that later became known as “serialism” and something which Zemlinsky opposed. As much as he was interested in the expansion of chromaticism – not to mention working with “numerology” – Zemlinsky was never comfortable with abandoning tonality completely: he felt that would be ignoring the spirit of nature. In the “Theme & Variations” of the 3rd Quartet, then, he parodies Schoenberg's new “serial” style.

By now, Zemlinsky's own musical voice had become less reliant on internal creative processes and more on external reactive impressions: from the imitations of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde to parodying Schoenberg's serialism. While the new operas he began composing at this time – when he had time – were lush, post-Romantic scores that often ended in some kind of utopian D Major, it was his last quartet that came directly out of his emotions but again inspired by external events: in this case, the death of his close friend, Alban Berg, who died suddenly just before Christmas of 1935.

By this time, Zemlinsky left Berlin with its increasing presence of the Nazi Party and returned to Vienna. His new quartet, started almost immediately after Berg's funeral, became a Requiem for his friend – just as his 3rd Quartet had begun as a threnody for his sister Mathilde. He was always more attuned to Berg's more flexible approach to Schoenberg's styles (both atonal and serial) and since Berg had quoted from Zemlinsky's “Lyric Symphony” in his 1926 string quartet, the Lyric Suite, and dedicated it to Zemlinsky, Zemlinsky in turn wrote a string quartet he subtitled “Suite” – like Berg's, in six movements – though without the intricate and highly personal program (which Zemlinsky was certainly unaware of). [For links to Berg's Lyric Suite, see the previous post for its references regarding the inspiration for Bartók's 3rd Quartet.]

It's not really “six” movements but rather three pairs of movements: each pair being, in a way, reflections of the same material but presented in different and often violently contrasting ways – the way, for instance, memories and a sense of grief can unexpectedly turn into incomprehension and rage.

The first movement serves the purpose, as an introduction, of both a chorale and a funeral march in music that reflects Berg's melodic style but sometimes, in the contrapuntal texture, a conversation of mourners. The “burlesque” of the second movement – in the sense of being a parody – with its scurrying frenzy (reminiscent of the famous 3rd movement of Berg's “Lyric Suite”), takes on an entirely different and often violent surface.

Preludium

Burlesque

The third movement, an adagietto, unwinds slowly in dense threads that might bring to mind Wagner's chromaticism by way of Berg's. In contrast, the Intermezzo is clearly a jazzy if at times delicate, understated dance, before breaking out in a slightly cheeky remembrance of good times past.

Adagietto

Intermezzo

As the Intermezzo's rowdiness subsides, the composer – represented by the cello solo – is left alone with his thoughts in what becomes the theme for a set of variations, a truly elegiac moment and the most personal music of the entire quartet (if not all four of Zemlinsky's quartets). The elegy – labeled “Barcarolle” or “Gondola Song” – is passed from one player to another, accompanied by a haze of reminiscences in the others.

The finale – perhaps thinking back not only to Berg's often complex counterpoint but also the performance Zemlinsky conducted in the mid-1930s of an orchestration of Bach's Art of Fugue – is a Double Fugue that parodies the motive that opens the Elegy. This again reminds me of an overt reference to Berg's Lyric Suite. The movement ends in a blast of “tonal resolution” with the fugue subject in unison, sounding less “modern” than Beethoven's Grosse Fuge and not, perhaps, what one might expect from a work with such mournful origins.

Theme & Variations: Barcarolle

Double Fugue

But as with his operas of the mid-'30s ending with their “utopian optimism,” perhaps even in such a state, Zemlinsky was not yet ready to end his memorial tribute with any sense of negativity – or abandonment of tonality despite the intense chromaticism of the rest of the work – to fade away into nothingness the way Berg ended his Lyric Suite, in desolation.

As luck (or lack of luck) would have it, Zemlinsky had little chance to write much more after this 4th Quartet. In 1938, when the Nazis occupied Vienna, Zemlinsky and his wife Louise fled once more, this time through Prague to Holland, arriving in New York City just after Christmastime, nearly broke. About six months later, he suffered a severe stroke and was no longer able to compose. Several subsequent strokes weakened his health. When his brother-in-law arrived from Europe in 1942 with the remains of his wife's family's fortune, they were able to buy a house in suburban New Rochelle. Four days after they moved in, Zemlinsky died at the age of 70.

It is not a pleasant story, this life, and after putting it together for you, I find I am even more curious about why Zemlinsky – receiving the support of Brahms and Mahler when he was in his 20s, and given the connections he knew – never realized his potential. It is hard to think of him as a failure – given the American attitude about competition, “you don't win the silver: you lose the gold” – but sometimes it makes you wonder why, for some, life (and fame) can be so unforgiving.

Dick Strawser