What: Quartets by Bela Bartók, Alexander Zemlinsky, and Antonin Dvořák

When: Sunday, Feb. 25th, at 4:00 with a pre-concert talk by Dick Strawser at 3:15

Where: Temple Ohev Sholom at 2345 N. Front Street in uptown Harrisburg (directions, here)

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| The Escher Quartet on the road (I'm sure they get more than a bicycle when they tour) |

So, as conversations evolved during their brief visit to Harrisburg, it was agreed the Escher Quartet would make its own scheduled appearance this season. For this visit, they're again playing Bartók and Dvořák but adding one of their own specialties, a quartet by Alexander Zemlinsky (they've recorded and perform all four as a cycle). This time around, it's Bartók's 3rd and Dvořák's last, the A-flat Major Quartet Op. 105, as well as Zemlinsky's last, his Quartet No. 4.

If you're not familiar with the Escher Quartet's playing, here are two samples recorded in 2015 from “Music at Menlo” – first, the opening movement of Mozart's D Minor Quartet which we'd heard just last month with the Jupiter Quartet:

...and with the Quartetsatz of Franz Schubert, that one movement he completed of a proposed C Minor String Quartet that should, by rights, be called the “Unfinished” Quartet:

And if you did miss the Escher Quartet's concert in 2016, here is the complete program recorded at their Market Square Church performance. The first video opens with the Mozart B-flat, K.598; the Bartók 2nd begins at 23:50. The second video contains the Dvořák Quartet in G Major, Op. 106.

= = = = =

(with thanks to Market Square Church's resident sound- and video-technician, Newman Stare.)

= = = = =

Here is a brief and very informal interview with members of the quartet recorded during a performance in Tel Aviv, talking about the importance of music in their lives as well as how they became the “Escher” Quartet and the visit backstage after one concert where a man named Escher introduced himself. You see, they decided the Dutch artist M.C. Escher with his distinctive dimensionally challenging style (see below), would be an appropriate name for a group that explores various dimensionalities in chamber music. And the man named Escher who dropped by after the concert was M.C. Escher's son, George.

This post will cover the Dvořák quartet: you can read about (and listen to) the Bartók Quartet in the second post, here; and the Zemlinsky Quartet in the third post, here.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| M.C. Escher, Waterfall (1961) |

For historical background and biographical information, you can read Lucy Miller Murray's always engaging program notes on the MSC website here.

And of course, you can read this post either before or after the concert and still find some enlightenment about the world behind the music.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Usually, I'd present the pieces in “program order” – as you'll hear them Sunday afternoon – but I decided for this one, I'd do them in “chronological order,” starting with the most familiar (Dvořák in 1895), then the less familiar (Bartók in 1927) and finally the least familiar and quite possible the unknown (Zemlinsky in 1936), all composed within a span of 41 years.

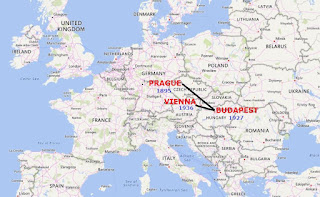

Or, for that matter, I could present them in, uhm... a kind of “geographical order,” working in toward the thematic center of Vienna: this would be Dvořák in Prague (which is 156 miles from Vienna as the crow flies, presumably first class); then, Bartók in Budapest (276 miles from Prague); and finally, in the center of it all, Zemlinsky's Vienna (135 miles from Budapest). Kind of an odd route as most tours go, but you'll see why this might work, in a bit...

To give you an idea of the space we'll be traveling musically in this concert, if we started in Pittsburgh, it would be 254 miles to Philadelphia and then 94 miles back to Harrisburg. The distance between Prague and Budapest is only 22 miles longer than it is from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

In April of 1895, Dvořák returned to Prague following his stay in the United States, teaching at the National Conservatory in New York City since 1892. While he was there he composed, among other works, the “New World” Symphony and the “American” Quartet (No. 12), but when philanthropist Jeanette Thurber's money ran out and her pet project, the conservatory, could no longer guarantee Dvořák his “then-staggering” annual salary of $15,000, so the composer (long homesick for his native Bohemia) quickly packed his bags and left for Prague, bags which included sketches for two nearly completed works he'd been composing at the time, the Cello Concerto (Op. 104) and what became his last string quartet, No. 14 in A-flat Major (Op.105).

He'd already been working on this last quartet for six months before he left New York, a rather long time for him. Then he began working on a new quartet which became the G Major, started in November, 1895, and completed on December 9th. This then helped him break through the issues he'd been having with the A-flat Quartet and he finished it three weeks later.

(Through one of those flukes, he was working on two quartets almost simultaneously: No. 14 in A-flat got to the publishers first as Op.105, so No.13 in G Major became Op. 106. Yes, the numbering indicates the order of their completion, but the opus numbers are off-kilter, always confusing. Dvořák was never one to care much about opus numbers and chronology.)

Here's a classic performance with the Cleveland Quartet:

= = = = =

The quartet is in the usual four movements. The opening Allegro appasionato begins with a brooding slow introduction before lifting the curtain on the scene easily described as “a pleasant homecoming.” The second movement is the scherzo, marked Molto vivace and full of the syncopations and cross-rhythms typical of the Czech dance called a furiant. The middle section, the trio, is one of Dvořák's sweeter respites.

The slow movement, Lento e molto cantabile (“slow and very song-like”), is based on a choral song Dvořák composed on Christmas Day (five days before he officially completed the entire quartet). Then the finale brings back the suspenseful mood of the introduction before quickly opening up into a joyous dance – again, the pleasure of a homecoming – before ending with a big, almost orchestral climax to what would become not only his last string quartet but his last chamber work.

Dvořák was 54 when he completed these last two quartets of his. Though he would live another 8 years, he wrote primarily orchestral tone poems and operas, leaving the “abstract” world of chamber music, symphonies and concertos behind for the story-telling world of symphonic poems, three of which, composed in quick succession, got their first performances (basically open rehearsals) four months ahead of the A-flat Quartet – and four more operas including Rusalka of 1900, a Slavic version of “The Little Mermaid” story, with its famous “Song to the Moon.”

When he died at the age of 62 following a bout of the flu in 1904, he left sketches for several works behind, including a couple of possible oratorios and three more potential operas, but no chamber music.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

As I suspected, this post would be too long by the time I get around to the remaining two quartets on the program, so I will continue with the Bartók and the Zemlinsky works in subsequent posts.

- Dick Strawser

No comments:

Post a Comment