Please note, this Sunday's concert with the Poulenc Trio is being held at the Derry Presbyterian Church in Hershey (PA) at 4pm – click here for directions.

|

| The Poulenc Trio |

Since they call themselves The Poulenc Trio and they're an ensemble consisting of an oboist, a bassoonist, and a pianist, it would be obvious Poulenc's Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano should be at the center of their repertoire. To be honest, it's more like “near the end of the program,” but I'll begin with it. Here is the Poulenc Trio playing the Poulenc Trio which Francis Poulenc completed in 1926 when he was 27:

Since I can't find the 3rd movement with the Poulenc Trio, here it is from a studio recording made in 1957 with oboist Pierre Pierlot, bassoonist Maurice Allard, and pianist, Francis Poulenc, now 58.

It's the usual “fast-slow-fast” combination of movements, but it begins with these very serious sounding chords in the piano, a little off-putting with their dissonances, perhaps, followed by the winds playing with almost operatic seriousness. Imagine hearing this in the mid-1920s as Late-Romanticism's lushness was giving way to a harder edged Neo-Classicism, the “New Classical Style” with what many of its contemporaries called “Wrong-Note Harmony.” It has the same clean lines of Mozart and Haydn's 18th Century, but with something... well... a little different. It's almost as if Poulenc were giving his "serious" listeners, as they say, the bird...

|

| Poulenc at 18 (w/bird) |

Francis Poulenc was a French composer, through and through – more specifically, a Parisian composer, born there in January of 1899 and dying there in 1963. But not just born in Paris: in the 8th arrondissment centered around the Champs-Élysées with the famous Arc de Triomphe at one end, a district known for its theatres, cafés, and luxury shops, if not the “Main Street” of Paris, certainly one of the most famous streets in the world (even if you only think of George Gershwin listening to taxi horns while sitting in a sidewalk café in 1926). No doubt Poulenc's growing up in the heart of this joie de vivre had some influence on his light-hearted musical style.

And because of this, Poulenc is often not “taken seriously” by serious-minded music-lovers. When showed his Rapsodie negre, Poulenc's first “serious” composition (considering the very first piece on his list of works was a "Procession for the Cremation of a Mandarin" from 1914), a professor at the Conservatoire thought the 17-year-old composer was trying to make a fool of him. It hardly got any better as he explored the various possibilities open to a young composer in the Paris of World War I at a time when Debussy was dying and Ravel was at his peak.

Poulenc's family was wealthy – manufacturers

of pharmaceuticals, in fact – and his mother was “an excellent

pianist” who started giving him lessons when he was 5. Her brother,

known to us as “Oncle Papoum,” introduced him to Paris' lively

theatrical life. Young Francis could recite Mallarmé from memory at 10 and at

14 was among those amazed at the premiere of Stravinsky's Rite of

Spring. At 16, he began studying piano with the great Ricardo

Viñes, a friend of Debussy's and Ravel's, and soon met some other

composers named Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, and Georges Auric

(they soon added two more friends including Germaine Tailleferre, to

form a group known as Les Six – as if their musical style

wasn't daring enough: a group of composers that included a woman!)

not to forget Erik Satie, a major influence, who was the front-rank

avant-garde composer du jour.

He tried studying with Ravel but that apparently didn't work out: Fauré, then the director of the Conservatoire, had an assistant, Charles Koechlin (much over-looked by American audiences today), who proved more sympathetic. Poulenc studied with him off-and-on between 1921 and 1924. “By mutual consent,” according to Grove's Dictionary, “Poulenc's involvement with counterpoint went no further than Bach chorales,” meaning he never bothered with fugue-writing, one of the cornerstones of the development of ones contrapuntal skills. His ballet Les biches was a huge success with Diaghilev's company in 1924. (The untranslatable title can be loosely translated as “The doe-eyed young ladies” though there was also the underworld slang of “someone, male or female, with 'deviant sexual proclivities'.”) In the meantime, he started several pieces of chamber music – easier for a young beginning composer to get performed than writing orchestral and operatic works.

|

| Poulenc in 1925 |

Poulenc never was comfortable writing for strings: he considered his one surviving Violin Sonata (his fourth attempt and the only one published, 1943) a failure, and he thought the Cello Sonata (written over a span of eight years in the '40s) would've sounded better on the bassoon. While a string trio and another string quartet would be trashed, one of his happier experiences with chamber music was the Sextet for Piano and... Wind Quintet!

While it's conceivable this Trio for Oboe, Bassoon, and Piano could've been written initially with clarinet and cello in mind, the infectious joy of the first movement and the heart-on-sleeve romance in the slow movement may have struck him later as better suited for the combination he ended up choosing. (Even in these post-Covid days, perhaps I should reconsider using the word “infectious”...) To get away from family distractions, he retreated to a hotel room in Cannes (to avoid distractions??). While there, he met Igor Stravinsky who gave him some helpful insights in how to handle some problematical moments in the first movement. Poulenc dedicated the newly finished work to his friend, Manuel de Falla. At that same time, he met Wanda Landowska who was re-introducing the harpsichord to modern audiences and she commissioned a new concerto from him.

|

| Poulenc (w/Mickey) |

Poulenc loved to absorb almost anything that caught his imagination. He might evoke the past or the new-fangled sound of jazz. His love of Mozart is evident through many of his works, even this trio: he opens the slow movement of his Concerto for Two Pianos, written in 1932, with a definite bow to Mozart but it quickly moves off into a style that is decidedly his own. There are, as well, tinges of jazz by way of Ravel's G Major Piano Concerto, premiered only a few months earlier, not to mention the appearance of the Balinese gamelan which he'd first heard the year before.

Even though his contemporaries might disparage his style, he himself was more open-minded than we might think. In 1921, he traveled to Vienna where he met Arnold Schoenberg and “talked shop” with him and his pupils (Schoenberg at the time was developing what soon became his “Method of Composing with 12-Tones”). A fan of Pierre Boulez, playing recordings of his Marteau sans maître for some friends, Poulenc wrote in 1961 how he was sorry to have to miss a performance of Boulez' recent Pli selon pli “because I am sure it is well worth hearing” (Boulez did not return the sentiment).

In 1942 he wrote to a friend, “I know perfectly well I am not one of those composers who made harmonic innovations like Igor [Stravinsky], Debussy or Ravel but I think there is room for new music which doesn't mind using other people's chords. Wasn't that the case with Mozart-Schubert?”

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| Viet Cuong (photo by Aaron Jay Young) |

“Audience members are in for a sound that they’ve never heard before,” according to the Trio's website. “Explain Yourself features what must be the most multiphonic oboe notes ever written in a tonal chamber music work. Multiphonics are a special playing technique where oboist Alex Vvedensky” (the oboist at the time it was composed) “will he heard to play multiple notes at once, similar to the ‘double-stop’ effect used by string instrumentalists. The multiphonic effect adds to the wild feeling that infuses the piece.”

“As a clarinetist and admirer of twentieth century French music,” the composer writes, “I’ve always loved the music of Francis Poulenc. I’m particularly drawn to the joyous, witty nature of many of his pieces, and, with this piece being for the Poulenc Trio (plus clarinet!), I wanted to pay homage to Poulenc and his sense of humor. As such, the piece actually begins with a direct quote of his chamber piano concert, Aubade. This quote serves a few purposes: it acts as a marker for when the first section “repeats” itself, and, perhaps more importantly, the main melody of the entire piece uses the same pitches as the opening of Aubade.

“After the Poulenc quote, the piece jolts into a tango-like romp with a baroque flair. The instruments all play an equal role in this music and, all things considered, it’s pretty mild mannered. After a few minutes, the Aubade quote signifies a trip back to the beginning after the first climax concludes— much like a repeat in a classical symphony’s first movement. However, this repeat goes awry as the oboist begins to act out by replacing regular notes with raucous multiphonics. The other wind instruments begin to pick up on this mischievous behavior, and all three of them start to interrupt, mock, and distort the phrases. The pianist notices and isn’t pleased. Much like a frustrated parent or teacher, the pianist hammers out dense chords, essentially scolding the winds to get back on track.

“Things nearly fall apart as the winds continue to misbehave. Eventually it all comes to a head when the pianist and oboist perform an imitative duet. In doing this, the oboist has a chance to explain himself and prove that, while these multiphonics can be funny, they can also be played melodically and provide structure to a phrase. Won over, the pianist joins in on the fun and the piece concludes in a place where functional classical harmonies and multiphonics can coexist.

“This piece was commissioned by the Barlow Endowment for Music Composition at Brigham Young University for the Poulenc Trio.”

While I couldn't find a recording available of “Explain Yourself!”, I decided to use this one to illustrate Mr. Cuong's musical versatility. After you've read the “humorous description” behind the music in the work you'll hear at Sunday's concert, this one, written in 2023, was inspired by grief and the composer's response to the loss of his father. “I felt as if I had lost my leaves,” he writes. “Many days I feared those leaves would never grow back. After struggling for months to write, I finally found some healing while creating Deciduous. This involved revisiting chord progressions that brought me solace throughout my life and activating them in textures that I have enjoyed exploring in recent years. The piece cycles through these chord progressions, building to a moment where it’s stripped of everything and must find a way to renew itself. While I continue to struggle with this loss, I have come to understand that healing is not as much of a linear process as it is a cyclical journey, where, without fail, every leafless winter is followed by a spring.”

(Deciduous by Viet Cuong, performed by the Texas Tech University Symphonic Wind Ensemble, Dr. Sarah McKoin, Director)

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

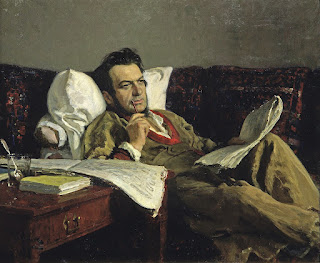

| Mikhail Glinka, painted by Ilya Repin in 1887 |

Mikhail Glinka's name is most likely familiar to many of you, if not his story. Some of his music is indeed famous – the operas, A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmilla, a few orchestral works, but most specifically, Kamarinskaya – but the “Trio Pathétique” may be unfamiliar territory. Written originally for clarinet, bassoon, and piano, it was published with an alternative ensemble, the traditional piano trio with violin and cello. That was the publisher's doing since he could make more money selling the sheet music to amateur string players than there would be clarinetists and bassoonists looking for things to play (that's the reason violists can thank Brahms for writing two viola sonatas at the end of his life: the publisher saw little chance of any income from stuff for clarinet!). So it's not illogical to find an oboist and a bassoonist appropriating some other combination's repertoire (I refer to the previous concert with all the transcriptions for Cello Quartet!).

It's in four movements with the scherzo in second place, but there's a break between the slow movement and the spirited finale. For Mozart, D Minor was a dramatic key – his demonic D Minor Piano Concerto and the statue music of Don Giovanni (G Minor was, for Mozart, the tragic key); Glinka's finale might seem more despairing, like a heart-broken lover taking leave of an ex-girlfriend perhaps?

|

| Glinka in 1840 |

In Glinka's case, after the first performance, the bassoonist told the composer (in Italian) "Ma questo è disperazione!" Again, this is not so literally desperation as in "feeling desperate" – imagine playing the “Desperation Trio” – as despair. Given the first publication of the piece wasn't until 1878, 21 years after the composer's death, whether it was known (if known at all) in the interim as the Trio Pathétique, I can't say, but the publisher prefaced the score with a quotation in French from the composer himself: «je n’ai connu l’amour qu’à travers le malheur qu’il cause» ("I have only known love through the misfortune it causes") whether the title was his suggestion or not.

Given Glinka's habitual womanizing, however, this might make more sense, as one commentator suggested, “[evoking] the trail of amorous spite”. Other adjectives often attached to the composer are “indolent, self-indulgent, a hypochondriac, and a libertine who wasted years of his life in dissipation, the pursuit of women, or simple idleness,” and we might see the title in a more comic light, given the light-heartedness of most of the piece rather than tragic. But then Tchaikovsky's symphony is not entirely “one of sadness” given the third movement's rousing march, the second movement's nostalgic 5/4 “waltz” or even the drama of the turbulent conflicts throughout the first movement.

Stylistically, given Glinka's future reputation and the fact that, in 1832, he hadn't had a chance to find his voice yet (always an elusive adventure for any young composer), this early work of his sounds more like Spohr or, in parts, Weber, or for that matter any of the hundreds of other once popular composers of the day who are now largely or entirely forgotten. Who listens to someone like Moscheles, Herz, or Kalkbrenner these days without thinking “Chopin did it better”? On the other hand, checking out Kalkbrenner's 4th Piano Concerto from 1835, it's an appealing and delightful piece, thoroughly entertaining: what would be wrong with hearing it once in a while instead of something that's constantly overplayed? Yes, well... moving right along...

Speaking of hindsight, if you're familiar with Glinka's name and a few of the few pieces he left us, you might expect some “really Russian-sounding music” here, comparable to the Overture to Ruslan and Ludmilla or his brilliant dance-piece Kamarinskaya, perhaps the last work he completed, which has been called “the acorn from which the mighty oak of Russian music grew” (Stravinsky's usually given credit for that) but Tchaikovsky had said much the same thing much earlier. In fact, if you want to talk about the direct influence of Glinka on the young, developing Tchaikovsky, the finale of his 2nd Symphony (now re-translated as “The Ukrainian Symphony”) with its repetitive folk-song melody, is a direct descendant of Kamarinskaya.

“But,” you'll think while listening to Glinka's trio, “there's nothing remotely Russian-sounding here!” And that's basically because, quite simply, it was written before he discovered himself to be a composer of Russian music. Or for that matter, before any Russian-born composer had made the same discovery!

Unfortunately, that involves reams and reams of historical and cultural background: if you want, I could suggest a few very fat books that would delve into the question, “What Makes the Music Russian?” Suffice it to say that, at the time Glinka was growing up, there were no music schools in “all of Russia.” In fact, there were no music schools in Russia until two years after Glinka died – at the age of 52, btw – when Anton Rubinstein, a Russian pianist and composer who was, he lamented, “too German for the Russians and too Russian for the Germans,” founded a Music Society in Moscow and subsequently a branch in St. Petersburg that became conservatories. Among the first graduates was a young law clerk named Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky.

So technically Glinka did not have the resources a conservatory-trained student would have had. Nor did he, like Beethoven, have the support of the immediate past with models comparable to Haydn and Mozart and centuries of Germanic culture. There were no Russian composers, for the most part, and those that were were, like the architects who built St. Petersburg or the choir-masters who trained the singers in the Imperial choirs and theaters, imported from Italy. Yes, they slapped an onion-shaped dome on a church tower and called it “Russian” but that's about the extent of it. Those singers trained by Italian choir-masters (who were often also composers) sang Italian operas and those who began writing their own operas – even the Empress, Catherine the Great, wrote some librettos for them! – wrote in the Italian style.

In his epic novel War and Peace, Tolstoy points out how aristocrats spoke French rather than Russian and it was Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 that sent Russia's nobility scrambling to learn Russian (which they considered a “brutish” language) so as not to appear to be siding with the enemy. If you've read War and Peace, that most Russian of Russian novels, there are great swaths of French, even in the original Russian publications, stretching across the opening scenes as members of the Imperial elite gather to party and discuss the latest news from the Continent as Russia finds itself being dragged into the Napoleonic conflict of 1805.

And Glinka was born in 1804 on the estate of his father, a retired army colonel and member of this landed gentry, whose lands had been part of the family since the mid-1660s. The fact this estate, near Smolensk, was on the route Napoleon's troops took in 1812 during the course of their attack on Moscow and more importantly on their disastrous retreat following the burning of Moscow (“scorched earth” and the Russian Winter were two of the Russian armies most successful secret weapons). Russia was beginning to awaken, culturally, with this generation, but it was a long and very slow process, not an overnight blossoming, following centuries of isolation from Europe, largely begun around 1700 by Tsar Peter I (known as “The Great” to the West; to the Russians, not so much).

Growing up in this hot-house environment of the aristocracy, Glinka was not expected to “work” except as a military officer or a court minister (given the Byzantine bureaucracy that presumed to run this vast country), neither of which appealed to him, hence the idea of his being “indolent.” If you're interested in a Russian novel that won't make you want to slit your wrists, I strongly recommend Goncharov's Oblomov where a “thoroughly superfluous man” of the gentry class spends the entire first part of the novel lying in bed trying to think about the day ahead, “raising slothfulness to an art-form,” yet without making any decisions about what needs to be done (he's basically the patron saint of procrastinators – btw, I've been meaning to reread this novel for years, now...). It was begun during the mid-1840s when Glinka was trying to find his artistic voice, and published in 1859, the year Rubinstein founded his Moscow Music Society and school.

Raised first by his hypochondriac of a grandmother until around the age of 10, he then went to live with his uncle on a nearby estate where there was a small orchestra which played Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (who had written his Eroica in 1803). But in addition to hearing the peasants singing folk-songs with their crude traditional, often dissonant harmonizations, it was a clarinet quartet by Crussel (a Finnish-born composer of German heritage and training) that caught the boy's interest, and so he was then given music lessons on the piano and the violin. When he was sent to the Imperial Capital to attend a school for “aristocratic youth” at 13, he also widened his musical exposure, including all of three lessons with the Irish pianist John Field, the true “inventor” of the Nocturne who, as Clementi's traveling assistant, had been abandoned in Petersburg but stayed on to pursue a career as a concert pianist and teacher (in 1818, he left for Moscow where he stayed until returning to Europe four years later).

But the city was full of wealthy amateurs who amused each other with in-home performances and who wrote their own music imitating the more popular composers, mostly melancholy songs and fancifully titled piano pieces. Glinka, having no recourse to professional music-making otherwise, fell into this culture and wrote a great many such pieces himself – salon music, it's usually called, with the same dismissive air we unfortunately treat the word “amateur” today (sniff...). (In the 19th Century, the term amateur had nothing to do with the quality of the artist, but rather with the fact they were doing it out of love (hence, amo – amateur) rather than for financial gain. As aristocrats – especially as aristocratic ladies – it was also unseemly they should pursue an actual career in it!)

As for his bureaucratic career, young Glinka was appointed as an assistant secretary in the Department of Public Highways (RUSSdot, I guess you could call it), having failed to gain entry into the more prestigious Foreign Office. The rather light demands of his work-life did not impinge on his becoming a leading dilettante in Petersburg. But when in 1830 his physician suggested a trip to Italy for his health, he ended up in Milan (then part of the Austrian Empire) where he attended some classes at the conservatory and was so bored with the academic work – the study counterpoint has nearly killed more than one budding composer – he found a new hobby: hanging out with singers, especially romancing the ladies. With this new crowd, he met composers like Berlioz and Mendelssohn – both were in Rome at the same time, working on their Fantastique and Italian Symphonies respectively – and followed one soprano, a Russian, to Naples and sat in on her voice-lessons where he learned some of the techniques involved in bel canto singing (a vocal style that also greatly influenced Chopin). While in Naples, he also met Donizetti and Bellini who were in town for the premieres of their Anna Bolena and La sonnambula respectively. However, bored with Italy, he traveled by way of Switzerland to Berlin where he met Siegfried Dehn, a well-known theorist, with whom he began serious study of composition.

Dehn, Glinka later wrote, “not only put my musical knowledge into order but also my ideas on art in general, and after his lessons I no longer groped my way along, but worked with the full consciousness of what I was doing.” This was in 1833. The following spring, word arrived that Glinka's father had died: he must return to Russia and the estate he'd now inherited.

So while he'd been in Italy – specifically Milan – hating counterpoint and not taking his music education too seriously, the then 28-year-old Glinka wrote a trio for some friends of his: he played the piano, with Pietro Tassistro, the clarinetist, and Antonio Cantú, the bassoonist. They were not amateurs but members of the orchestra at La Scala.

Whatever the subsequent history of this piece may have been – keeping in mind, the following year Glinka left Italy and decided to pursue the study of composition in earnest – its publication as late as 1878 was due to Glinka's long-suffering younger sister, Ludmilla (she died in 1906!) who had frequently acted as his nurse during his various illnesses. Returning to Berlin and just resuming his studies with Dehn after having heard the Crucifixus from Bach's B Minor Mass, he caught a cold and died at the age of 52 – I can just hear the hypochondriac now: “I told you I was sick!” It was Ludmilla who had him reburied in Petersburg. She had always been urging him to compose whenever he would give up in frustration, especially after the failure of his second opera, Ruslan and Lyudmilla, so it was perfectly natural she spent the decades following his death trying to keep his music alive.

Failing to convince the authorities to stage Ruslan in Petersburg, she sent a young friend of hers to Prague, hoping to mount the opera there and maybe impress the Russian opera houses to take it more seriously. Eventually, it worked, but not until 1872. There was only one copy left of A Life for the Tsar, his first opera – which was a success – so she had this same friend and a couple of his friends make two new copies of the score; and just in time because shortly afterward, there was a fire at the Imperial opera house and the original manuscript was lost in the flames!

By the way, these young friends of Ludmilla's? The one sent to Prague was Mily Balakirev, and one of the copyists was Modeste Mussorgsky. Soon, there were a few more gathering at Ludmilla's home for musical discussions and performances who would become the nucleus of a bunch of composers forever known as The Mighty Handful – or more famously, The Russian Five.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

|

| Shostakovich (front, right) watching a football match |

A much better known Russian composer is Dmitri Shostakovich and thanks to Stuart Malina's love of his symphonies, we've heard quite a few of them with the Harrisburg Symphony over the years – most recently the 6th earlier this season. But the music on the Poulenc Trio's program – perhaps in deference to the typical joie-de-vivre of their namesake – is not the Shostakovich of those slowly unwinding, expansive, often gloomy opening movements typical of so many of his symphonies, well-known for their often dark and always intense emotional underpinnings. There is, contrary to what you might assume, a lighter side to Shostakovich – and more than just the tongue-in-cheek naughtiness of the Polka from the ballet, The Age of Gold.

His Moskva Cheryómushki is basically a Soviet equivalent of a Broadway Musical though it's called an operetta (less serious than a real, all-out opera) – just as his “Jazz Suites” are not so much Western jazz as English dance-hall tunes! And when you listen to this, if it's new to you, I defy you to win a “Name That Composer” contest – or even realize this is RRRRussian Music!

Here's the Poulenc Trio in a 2019 performance recorded at Peabody in Baltimore:

Ostensibly, the show's plot focuses on

the typical Soviet citizens' never-ending search for livable housing

conditions. Cheryómushki is a real place, a subsidized housing

development in Moscow full of cheap houses built in 1956. There are

seven “good” characters and three villains which include a

colleague of the hero's who's conniving to get the apartment first,

the corrupt developer (a petty bureaucrat), and an equally corrupt

low-ranking estate agent who refuses to give over the key. The scene for "A Spin Around Moscow" describes the delight of the "good characters" as they are driven across town, no doubt careening through winding streets, to see their new home.

And what did the composer think of this step outside his typical symphonic comfort zone?

Before the premiere, Shostakovich wrote to a friend, “I am behaving very properly and attending rehearsals of my operetta. I am burning with shame. If you have any thoughts of coming to the first night, I advise you to think again. It is not worth spending time to feast your eyes and ears on my disgrace. Boring, unimaginative, stupid. This is, in confidence, all I have to tell you.”

Well, yes... enough said... moving right along...

The Poulenc Trio prefaces this with a “Romance” – in Russian, the word for “song” is “romance” just as in German it's Lied – taken from his 1955 film score for the Russian thriller, “The Gadfly,” based on an 1897 novel by Ethel Voynich set in the 1840s during the Italian attempts to dispel the occupying Austrian forces. Again, the plot is not important to enjoying the melody Shostakovich wrote, here – you can read the plot summary if you're curious – but, not being familiar either with the novel or the film or who's involved in this particular scene, I'm curious about the motivic references to Schubert and Schumann I hear in it; not that all Russian music (even Soviet music) needs to sound like a peasant dealing with lost love or a harsher-than-usual winter...

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

Handel and Rossini may frame the program, but I'll end this post with them.

The trio sonata as a “form” –

more correctly, a genre – was sort of a default setting in the Baroque Era.

Typically, it consisted of four players

because, in Baroque music, the role of “the continuo” was always played

by two instruments, an instrument that could play harmony like a

harpsichord or organ, and another to emphasize the all-important bass-line of

the harmony with a cello, bass, or bassoon. If

the piece was played in a church, they'd use the organ; in some

aristocrat's music room, a harpsichord – or, for that matter, even

a lute of some kind. The two “melody instruments” playing over

this accompaniment were normally violins, but it would be possible to

use, say, a violin and a flute or oboe, or a pair of wind instruments,

matched or mismatched. It really didn't matter: the music was not

specifically composed to suit the violin the way Beethoven or

Paganini would later write for them.

With the Poulenc Trio, their solution

was to use a modern day piano, of course – still, a transcription

given the difference in technique needed to play a harpsichord or

organ – but also to use the bassoon not as a continuo instrument but as one of the "melody" instruments, even if they're not playing in the same octave like a pair of flutes.

And now to conclude, finally, with a Fantasy on Rossini's L'Italiana in Algeri, here recorded by the Poulenc Trio in Baltimore, 2021:

Officially, this last work on the program is one of those “bring-the-house-down” bravura concert fantasies based on themes from other composers' popular works. In this case, oboist Charles Triébert and bassoonist Eugène Jancourt, both famous teachers at the Paris Conservatoire and highly acclaimed performers adapted some of the greatest moments from Rossini's opera, L'Italiana in Algeri (“The Italian Girl in Algiers”), originally written in 18 days in 1813 when Rossini was 21. Incidentally, Triébert also improved the fingering system for the oboe in 1855 and Jancourt brought various improvements to the bassoon to make it a more reliable solo instrument, especially improving the upper register – another reason both men should be remembered fondly by oboists and bassoonists of today.

While

one could argue the music

Jancourt and Triébert adapted for their “Fantasie Concertante”

was by Rossini, the way it was presented – particularly with its

virtuosic cadenzas and technical passages – was entirely their own,

transcending the art of arranging and going beyond the original roles

assigned to the singers. I don't know if anyone every called Triébert

the Paganini of the Oboe or Jancourt the Franz Liszt of the Bassoon,

but it would amount to the same thing, given the number of such

fantasies that frequently appeared on their concert tours like Paganini's

Fantasy on the G String from Rossini's Moses and

Liszt on... well, to pick just one, let's say his Concert Paraphrase

on Verdi's Rigoletto.

And now, moving right along... enjoy the concert!

– Dick Strawser