|

| 1698 Publication honoring Henry Purcell as the English Orpheus |

Best Regards,

Peter Sirotin & Ya-Ting Chang, Market Square Concerts Co-Directors]

= = = = = = =

Now that we have survived another Holiday Season, past Thanksgiving, Hannukah, Christmas, New Years Eve and are running headlong into the new and even more unknowable New Year of 2022 amid the on-going Pandemic, here we are with the first program of that New Year at Market Square Church on Wednesday Night, January 5th, at 7:30.

The program is billed as “A Cabaret of Love” called “English Orpheus,” its creative concept originated by the group's lutenist, Richard Stone. It will be performed by the “early music ensemble,” Tempesta di Mare Chamber Players, a Baroque orchestra from Philadelphia who take their name from Vivaldi's famous set of concertos subtitled “The Storm at Sea.”

Here they are, performing excerpts from a Handel Trio Sonata (Op.2, No.5):

Consisting of pairs of recorders and violinists, a cellist, a lutenist, a player of that curiously English Renaissance keyboard instrument called the virginal (see below), not to forget a tenor, the ensemble will be joined by two actors from Harrisburg's Gamut Theatre, Alexis Dow Campbell and Robert Campbell directed by Clark Nicholson, reading selected poems and texts associated with the theme of The Program.

And what better way of introducing the program than by quoting the notes by the ensemble's artistic directors, Richard Stone and recorder-player Gwyn Roberts:

= = = = = = =

From time to time Tempesta experiments with alternate approaches to presentation, like No Strings Attached (2008), staged operatic vignettes by Monteverdi and Handel acted out by bunraku puppets, or our talk show from the Telemann 360° festival (2017). One performance form that has long stood on our to-try list has been cabaret. We have no illusions on hitting the high bars that the likes of a Noel Coward or Liza Minelli could make out of an evening with their inimitable forms of cabaret. But we do hope that, in our own nerdy way, our one-act experimental presentation of spoken word, song and instrumental music will stand apart from the traditional, classical recital form, and possibly even turn out as a successful iteration of its kind.

We have programmed English Orpheus along an arc of emotional themes, without consideration of chronology or even of composer groupings. Our programming followed the dictum of Giulio Caccini (1551–1618), one of the founders of the movement that defined baroque music: “prima la parola”, words first. Lyrics that expressed the themes that buttress our arc took center stage, though all in settings by some of England’s best composers.

We placed two restrictions on our programming. First, all the featured music had to be in English. Second, we limited the music to four composers—John Dowland, Henry Purcell, John Blow and George Frideric Handel—who were compared to the likes of Orpheus, Amphion and Apollo during their lifetimes. We allowed exceptions to the rule for the music that accompanies the recitations, such as “Simple Simon” and the song from Twelfth Night.

Orpheus and Amphion were more than musicians in classical Greek and Roman mythology; they were superheros, and music was their superpower. Orpheus’s singing charmed the king of the underworld to restore his deceased bride to life. Horace speaks of Amphion, who “built Thebes’ citadel, moved stones at the sound of his lyre, and set them where he wished with its charmed entreaty.” Both learned to play the lyre from Apollo, patron god of music.

One “English Orpheus” acknowledgement for lutenist John Dowland (1563–1626) appears in the dedication of a pavane by the Landgrave of Hesse to “Joanni Doulandi, Anglorum Orphei” in the publication A Variety of Lute Lessons (1610).

John Blow (1648–1708) and his one-time student Henry Purcell (1659–1695) were colleagues and lifelong friends. They borrowed material nearly exclusively from each other from the 1680’s onwards, with Blow more often the originator and Purcell the borrower. Poet John Dryden (1631–1700) called Purcell “our Orpheus”, while poet and orator George Herbert (1593–1633) marked Purcell’s death with the words, “thus Orpheus fell.” Of the teacher, Thomas D’Urfey wrote, “So whilst Apollo’s Race can Sing, / Great Blow will be true Musick’s King.”

Following the publication of Orpheus Britannicus (1698), a posthumous anthology of Purcell songs, Blow released a songbook of his own, Amphion Anglicus (1700). Blow knew that posterity would grant his friend the greater fame as attested by the parallel titles of the songbooks. The Orpheus/Amphion pairing reads as the master happily adopting the moniker of the less famous musical hero in deference to his stellar disciple.

Written comparisons of George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) to Orpheus were a constant through his career, but perhaps the most iconic is by sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac (1702–1762), portraying a relaxed Handel, absorbed in thought while plucking the emblem of Orpheus, the lyre. This was England’s first lifesize statue of a living artist, a German who became a naturalized Briton, and was installed in Vauxhall Garden in 1739.

– Richard Stone & Gwyn Roberts

= = = = =

Here, tenor Jacob Perry joins the chamber players for Henry Purcell's "Strike the Viol, Touch the Lute" from his ode, Come Ye Sons of Art.

While ordinarily I would be writing about the historical context of a given composer and the various compositions on the program, in this case, given the concept of the presentation, let me give you a kind of vague time-line to place each person on the program, composer or poet, in some chronological context rather than in concert-order – a different layer of context – along with the various rulers of England for some additional historical placement. While we think of the Age associated with Elizabeth I's reign, even if we never get beyond Shakespeare, or that her successor James I brought about the “King James Bible,” it might also be interesting, without going into too great detail, to realize what was going on in between those decades of English history and the years that saw the Renaissance evolve into the Baroque and the heady days of Handel and his Water Music, as the Stuarts and the Restoration (with the execution of one king and the deposing of another) gave way to a string of Georges bringing us up to the time of the American Colonies. While this program begins musically with Handel, he is the last of the line, here, chronologically. And let's not forget that he died in 1759 when a three-year old boy named Mozart was only a few years away from writing his first compositions.

= = = = = = =

Normally, in the modern-day world of Classical Music Programming and Standard Repertoire, we'd find ourselves limited to music from the time of Bach and Handel, through Mozart and Haydn in the 18th Century, from Beethoven and Schubert through the 19th Century, maybe a nod toward the 20th Century, and now taking more notice of our own times (at 22 years, the “New Century” isn't really that new any more, is it?).

So if we look at the basic dates on this program, we might consider it “Early Music” and lump it all together as “Old.” I've talked to many music-lovers over the decades who, enjoying Classical Music and often avid supporters of the Arts in the local community as they are, would be hard-pressed to think that Brahms and Mahler could overlap and even have known each other or that Mozart and Tchaikovsky weren't more than a few decades apart. If you, as I did, grew up during the Viet-Nam War and all this country went through during its course, it's sometimes confusing to realize that recent college graduates who weren't born then consider it all Ancient History. Perspective, like Time, is everything...

This program covers artists – beyond the ever-timeless Trad – whose careers ranged roughly between the 1550s and the 1750s. But that covers 200 years. So, from perhaps looking at these names and their more-or-less distant fame as being “limited” to Early Music and stereotyping them as more or less similar, let's imagine if the evening's repertoire consisted of music with a similar, more recent historical range. Instead, it could cover music from Mozart's “Haydn” Quartets to, say, Philip Glass's Koyaanisqaatsi. And how much variety is there in the music we listen to from those two centuries in between?

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

The Elizabethan Age: the 16th Century

The earliest-born of our personalities is the composer William Byrd whose actual birthdate is vaguely ascribed to somewhere between 1539 and 1543, give-or-take. Born during the reign of King Henry VIII, Byrd then would've been born somewhere before the king's marriage to Wife No. 4, Anne of Cleves, and around the time he'd married Wife No. 6, Catherine Parr. More important was his devotion to the Catholic Church, despite the turbulent on-again/off-again years of Henry's English Reformation and – overlooking the brief cameo of Henry's son, Edward VI, who became king when he was 9 and died at 15 – and Henry's two daughters, Queen Mary I (who was Catholic and married to the Defender of the Faith, Philip II, King of Spain), and then the enforcement of anti-Catholic measures during the reign of Anne Boleyn's daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. At times, simply being Catholic meant automatically you could be considered an Enemy of the State.

In 1572, Byrd became a member of the Chapel Royal, a body of musicians who accompanied the court and saw to the rulers' spiritual needs – and yet it was during the 1570s that his involvement with the Catholic church evolved. He composed a great deal of religious music, much of which had “a strong Catholic undercurrent” which, along with his associations with prominent Catholic families, got him suspended from the Chapel in the 1580s, placed on a watch list with his house frequently searched.

Perhaps to curry favor with the Protestant aristocracy, he turned to instrumental music for keyboard (such as the virginal) and for viols; and published two books of secular songs – “consort music” – for voice or voices with the accompaniment of a “consort” usually of viols. Yet later, in the 1590s, he also wrote three settings of the Catholic mass while still writing works for the Anglican service. The creator of at least 470 compositions, Byrd clearly was a complicated man who lived in complex times and yet managed to, in the long run, having lived into his 80s, become regarded as one of the greatest musicians of his day and one of the leading composers of the English Renaissance.

(By the way, what exactly is a “virginal”? Given Elizabeth I as The Virgin Queen, does the instrument's name refer to its pure, chaste sound or that it was intended to be played by demure young ladies to wile away the hours at home? Actually, sorry to disappoint: it's from the Latin virga or rod, referring to the mechanism by which a rod attached from the end of the key to a plectrum (or “jack”) then plucks the string. The instrument was placed on a tabletop; later, legs were added to create a larger, more resonant instrument. Popular especially in England during the Renaissance, it was a “private” instrument since its sound often could not reach the opposite side of a room, much less work in a concert hall – keeping in mind, in those days, concert halls did not yet exist. The term “virginal” could also be applied loosely to any keyboard instrument, whether harpsichord, clavichord, or “spinet.”)

|

| Flemish virginal on a grand scale, 1583 |

Of course, nothing says “Elizabethan Age” like the name, William Shakespeare, undoubtedly the most famous writer – poet and playwright – in the English language. And yet we know so little about him, actually; and what we do know – like, what is that bit about the “second-best bed”? – is not only vague but mysterious for someone so famous. Given the program, I'll mention that the three works representing him were written between 1601 and 1613, spanning the last years of Elizabeth I's life and the start of her successor's reign, James I. By the way, James was the son of Elizabeth's primary rival, her cousin Mary Queen of Scots, whom she had had executed for plotting to overthrow her: did those who first saw Macbeth in 1606, only a few years after Elizabeth's death, see the three witches' prophecy that Banquo's children would become kings of Scotland following his murder as political commentary on the children of Mary Queen of Scots now becoming Kings of Scotland and of England?

|

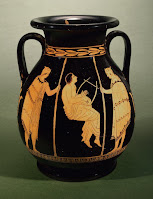

| Orpheus Vase, 430 BC |

= = = = = = =

It is a text that would inspire many musicians in future centuries, the perfect evocation of the legendary Orpheus of Greek mythology and of the power of music. And it will appropriately be followed by a work by Henry Purcell who was memorialized as “The British Orpheus” by his own colleagues when he died at the end of the 17th Century.

Shakespeare's “Sonnet 128,” from a set first published in 1609, deals with “The Dark Lady” whom the narrator (presumably but not necessarily the poet himself) observes playing the keyboard instrument known as the virginal, “captivated by her back swaying with the melody. Like Romeo [in the play of 1597], he longs for a kiss, but in this sonnet he envies the jacks (wooden keys) that the lady's playing fingers "tickle" while trilling the notes. Perhaps he also envies the other men (Jacks) standing around the lady. Surely, this is an amusing scene to the narrator because he secretly is having an affair with the dark lady. He decides not to envy those keys—although he would like to be tickled as they are—but hopes instead to receive a kiss on his lips.” Suitably, this recitation will be accompanied by William Byrd's set of variations on the traditional song, “John [another Jack?], come kiss me now.”

The play Twelfth Night is a comedy set on the festival that ends Christmas' twelve nights (back in the days when Christmas began on Christmas Day and, golden rings and leaping lords aside, they weren't hoisting dead, dried-up trees, now devoid of decorations, out to the curb on December 26th and putting away the holiday music for another year). Twelve drummers notwithstanding, the festivities were dominated by a Master-of-Ceremonies called “The Lord of Misrule.” And so the play appropriately “combines love, confusion, mistaken identities, and joyful discovery,” however improbable the theatrical conventions make some of those details seem to us. Written around 1600 or so, it was first performed publicly on Candelmas, Feb. 2nd, 1602 (the official end of the Christmas Season), but reportedly performed privately at Queen Elizabeth's 12th Night celebration at Whitehall Palace on January 6th, 1601. (Incidentally, while she died in 1603, Elizabeth's health did not begin to decline dangerously until 1602. One hopes the old girl – she was only 69 when she died – enjoyed these revels.)

(Speaking of misrule, if you are a fan of that odd-ball BBC comedy seen locally on PBS, Upstart Crow, Shakespeare's complicated artistic life as well as what one might guess about his personal life is often lampooned to the point of absurdity but, the more I watch it, I wonder, conjecture aside, how close to the truth it might be? In one episode, Will realizes he needs to bring in the adoring crowds, and so should “invent the musical,” coercing the popular singer Thomas Morely into supplying some tunes. Keep this in mind as you read through this next bit about another popular musician of Shakespeare's day. Imagine one of of those what-if brain-storms where John Dowland could write the songs for Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew: The Musical? Perhaps far-fetched but also possibly closer to the truth than we might think. Not that Shakespeare ever wrote a musical comedy, but music – both songs and dances – had a prominent role in his plays, as did, for instance, bits of comic relief in the midst of his tragedies (just think of the porter's brief monologue, answering the castle gate immediately following the murder of the king in Macbeth!)

Certainly, one of the most popular musicians of the era was John Dowland. An exact contemporary of Shakespeare, his career found him working for a British ambassador in Paris in the 1580s where he converted to Catholicism – like Byrd, this also caused some trouble politically (was his application for an appointment to the Court of Queen Elizabeth denied because of his religion?) but he was not as open about his religious practices as many others. In 1592, he became a lutenist to the King of Denmark who so enjoyed his music, he paid Dowland an astronomical salary, making him the highest paid courtier in Copenhagen. But he apparently abused his popularity there and was dismissed in 1606 as “not an ideal servant” and returned to London. He had been publishing his music in London from the 1590s on, despite living in Denmark, and though he became a lutenist at the Court of James I in 1612 – around the time Shakespeare's Henry VIII – not much music exists from his last decade or so. His last paycheck from the Court was dated January 20th, 1626, and his burial was recorded on February 20th.

Like Christopher Marlowe, another great playwright and contemporary (and friend) of Shakespeare's, Dowland, despite his religion, was employed as a spy by Elizabeth's minister, Sir Robert Cecil, who had developed the equivalent of a Secret Police and espionage network for the Royal Court (he was the one who uncovered the infamous Gunpowder Plot of 1605, intent on blowing up Parliament and assassinating the new king). As a Catholic at the Court – even the Queen called him “a man [fit] to serve any prince in the world, but [he] was an obstinate Papist” – Dowland was occasionally on the receiving end of bribes and plots from exiled Catholics on the Continent bearing money and guarantees of safe-passage from the Pope, but he remained loyal to his Queen.

His primary musical influences were the popular dance music of the day and the sad “consort songs” that often brought his audiences to tears, despite his being a generally happy personality, himself. In this sense, he was much like a “rock star” today, writing more for fame (and fortune), perhaps, than, like William Byrd or John Blow, as an artist. Even Shakespeare, while writing his tragedies and histories, was mindful of the need to “bring in the audience” with his comedies like 12th Night or The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Michael Drayton, another contemporary of Shakespeare's, published a volume of spiritual poetry in 1590 that earned a public order from the Archbishop of Canterbury that it be destroyed, and only 40 copies survived (not a great review). Nonetheless, he published sixty-four sonnets in 1594 under the title, Idea's Mirror, of which No. 61, “Since there's no help,” has become his most famous work. His “smooth style” foreshadowed several of the later Elizabethan poets: and keep in mind, Shakespeare's sonnets were published in 1609, some 15 years later.

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** *** ** * *

The 17th Century, an Age of Execution, Republic, and Restoration

In an age when kings believed themselves ordained by God – the “Divine Right of Kings” – King Charles I, son of King James I, was overthrown and executed following a series of Civil Wars, a very complex and violent period of English history. During the subsequent ten years of Republican rule, Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Puritan opposition, became a virtual dictator, and even after his death, it took two more years, his son following in his footsteps, before the Republic was overthrown and Charles I's son was brought to the throne as Charles II in 1660, beginning an age known as “The Restoration.” The age also saw two disasters in quick succession: The Great Plague of London in 1665 in which, at its peak, 7,000 people died in one week; and the Great Fire of London the following year, destroying over 13,000 houses including 82 churches.

Our next composer, chronologically, John Blow was born less than a month after Charles I was executed; and the little-known poet and courtier, Carr Scrope, about eight months afterward. Both went on to positions in the reign of Charles II, his brother, James II (who was deposed but managed to escape to France), and James' daughter Mary II (ruling with her Dutch-born husband, William of Orange).

Scrope, a minor aristocrat, was a courtier of short stature but “great wit” who “wrote with ease” and was popular among those hanging out with the glib King Charles II in London. While today, anyone who maintains a blog would consider himself a writer (ahem...), in those days, anyone who could put clever words into clever lines considered himself a poet. (One source described him as a "versifier" which is to "poet" what "fop" would be to "fashion icon.") Beyond being the butt of satire from rivals out to discredit those popular with the King, Scrope is probably best known for not much of anything. Perhaps the most interesting thing about him might be the fact he was buried in 1680 in the church, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, belovéd of 20th Century music lovers for its musical association with the Academy, a chamber orchestra which, over the decades, seemed to have recorded the complete works of just about everybody under the legendary Neville Marriner.

While the Elizabethan Age included many illustrious names among its dramatists, poets, and musicians, there are tons of (to us) unknown names for every famous one, whether it's Dowland, Byrd, Shakespeare or others too many to represent on such a program. Suffice it to say of Davis Mell, he was a clockmaker and a violinist, good enough to have not only played in the King's “Four-and-Twenty Fiddlers” (Old King Cole aside, copied from the French court's similarly numbered band) during the reigns of both Charles I and Charles II, but also to have led the ensemble for a while. A number of the pieces he wrote for the kings' entertainments were published in 1659.

John Blow is far more important, even if today he is remembered more for his association with Henry Purcell. He was an organist at Westminster Abbey (where he is buried) – he retired to make way for his student, Purcell – and later became a member of the Chapel Royal to Charles II and music teacher to the royal children (an odd position considering Charles had no legal heirs but a dozen illegitimate ones). Blow's masque – an early not-quite-a-modern opera – Venus and Adonis was staged in 1683 (in which Charles' current concubine sang the role of Venus, and her daughter by the king appeared as Cupid); in 1685 he became “one of the private musicians” to King James II. He became the choirmaster at St. Paul's and later returned to Westminster Abbey; in 1700, he became the newly-created Composer (-in-residence) to the Chapel Royal under William III (Mary II's surviving husband). He wrote over a dozen settings of the Anglican service plus more than a hundred anthems, fifty songs, and thirty odes for royal occasions. But he is best known for Venus and Adonis and the influence it had on Henry Purcell who composed what is arguably the first opera in the English language, Dido and Aeneas (and still in the repertoire today), no later than 1688, about five years after his teacher's work.

And so, a brief discourse on Henry Purcell, undoubtedly the greatest English composer before... well... considering Great Britain's lack of producing anyone comparable to Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner or Brahms which led Richard Strauss to call England “the land without music”... And if Benjamin Britten who died in 1976 was considered the “first internationally acclaimed British composer,” Henry Purcell is in rare company as the “Greatest English Composer” before the 20th Century and the likes of Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Holst, and William Walton as well! And it was Britten's love of Purcell's music – not just his “Variations on a Theme of Purcell” better known as “A Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra” – that brought Purcell to the attention of a much larger, modern audience.

Purcell was born in the slums of London in 1659, the middle of three sons. His uncle was a chorister in the king's Chapel Royal and who, after Purcell's father's death, took charge of the boys' education (Daniel, the youngest, also became a prolific and respected composer in his own right). Henry, according to legend, began composing at the age of 9, and, after attending the Westminster Abbey school and studying with John Blow, wrote his first setting of a psalm (for Christmas Day) which was performed when he was 19. Despite dying at the age of 36 – eight months after writing music for the funeral of Queen Mary – Purcell has a catalogue listing some 860 works. He was buried next to the organ in Westminster Abbey and lauded by his colleagues as “Orpheus brittanicus,” The English Orpheus.

In addition to Dido and Aeneas, he composed a great number of masques, odes, and incidental music for stage plays. Among his instrumental works are several trio sonatas – confusingly listed as “sonatas of three parts” and “sonatas of four parts” even though they're all “trio sonatas” meant to be played by four musicians (two violins and continuo which consists of two players, a cellist and a keyboardist, normally with a harpsichord or organ, hence four performers).

The Trio Sonata No. 3 in A Minor, from the second set (“Ten Sonatas in Four Parts”), is the earliest work by Purcell on the program. All twenty-two of these sonatas were written around the same time, about 1680, though not published until 1683 with a dedication to the king, Charles II. Purcell was greatly influenced by musical trends in France and Italy, though he never traveled there himself. While the earliest trio sonatas, for instance, date from 1607 with the Venetian Salamone Rossi, it is quite possibly Arcangelo Corelli's various sonatas that provided the impetus for Purcell to add a particularly English touch to the genre. Even though Corelli's weren't published until 1683, we know they were written by 1681, possibly earlier and may have been “hot-off-the-copyist's desk” arriving in London with some traveling musicians. It's not inconceivable that, impressed by this new style, Purcell was immediately inspired to examine the possibilities for this combination himself. Of course, there could have been other sonatas by other composers he'd come across earlier, but the opportunity for such cross-fertilization is not uncommon in the musical world. Bach, after all, was inspired by the discovery of concertos by Vivaldi and went and “did likewise.”

Each sonata is usually a collection of short movements, often continuous. One, my favorite, the G Minor sonata from the Set in Four Parts(Z.807), is a single-movement chaconne, not to be confused with the “Chaconny” also in G Minor (Z.730). Here is the one on the program, the sonata in A Minor (Z.804):

Of the “songs,” the earliest of the three on the program, “Music, for a while,” comes from the incidental music for the play Oedipus, written in 1692. “Strike the Viol, Touch the Lute” is part of the 1694 ode, Come, Ye Sons of Art. And “Sweeter than Roses” is a song from music for Richard Norton's play Pausanias, Betrayer of his Country about the Spartan general killed by his own people for his treachery. While Purcell and others may have contributed a great deal of music, instrumental and vocal, for certain plays, so much so they were sometimes referred to as “semi-operas” – (originating as a play to which music is added and, in many cases, filled in, would these constitute Upstart Crow's reference to “the first musical”?) – in the case of Pausanias, Purcell provided only one song and one duet for the 1695 production just months before he died.

William Congreve, born in 1670, and recognized as a leader of “Restoration Comedy” and especially the “Comedy-of-Manners,” bridges the gap into the new century: Purcell supplied incidental music for the 23-year-old Congreve's first play, The Old Bachelor, in 1693 (in this case, 9 dances and two songs). Described as a “sexual comedy of manners,” the play was a huge success, running for an unprecedented two-weeks at the Drury Lane Theater. I cannot find a date for the poem representing him on this program – “A Hue and Cry after Fair Amoret” – but he may be more familiar to us today through two famous quotes most often attributed to Shakespeare (as a teacher of mine said, “if a quote doesn't come from the Bible, it's probably Shakespeare”): (1.) usually rendered as something like “Music hath charms to sooth the savage breast” (though, given the image of Orpheus winning over the spirits of the underworld with his music, “savage beast” may be understandable if not simply a more prudish substitution) and (2.) likewise slightly misquoted, “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” Both originate in his 1697 tragedy, The Mourning Bride. He is also credited with originating the expression “you must not kiss and tell,” a line from his comedy, Love for Love, first produced in 1695. Though he lived until 1726, he essentially retired in his mid-30s to rest on his laurels.

(Incidentally, Jakob van Eyck, who's setting of “Simple Simon” accompanies Congreve's poem, technically belongs to the Elizabethan Age, born in 1590, and is not technically British. A Dutchman and blind from birth, he was a carillonneur, organist and recorder player who in 1644 published a collection of 143 pieces for recorder called “The Flute's Pleasure Garden,” ranging from arrangements of dance tunes and folk songs to several original works, including a set of variations of John Dowland's “Flow my Tears.”)

* * ** *** ***** ******** ***** ** * *

The 18th Century

And so, Purcell's death and Congreve's retirement bring us to a new century and a new shift in England's history, both political and cultural. With the last of the Stuarts, Queen Anne who was Mary II's sister had, like Elizabeth I before her, no immediate heirs (despite her seventeen pregnancies) and so the crown descended to her German cousin, George the Elector of Hanover who became King George I in 1714.

The story of George Frederic Handel (or Georg Frideric Händel) is much too involved for a short survey like this, so let me stick to a few pertinent facts. Born in Germany, he is technically not a British composer, though the majority of his career was based in England. And how could anyone who wrote The Hallelujah Chorus not be English?

After being appointed to the court of the Elector of Hanover in 1710, Handel almost immediately took a leave-of-absence to study in Italy, granted begrudgingly with certain conditions. It didn't win him any favor with his German employer when he decided he would follow up on an invitation to visit London where he produced his opera, Rinaldo, in 1711. A setting of a popular story set in the First Crusade and involving a tale of love, war, redemption, and a good deal of magic, it was a huge success, and so Handel decided to stay in England and seek his fortune there, reneging on his agreement with the Elector. If you consider what today we might call karma, how impossibly small the world must have seemed to the young Handel to find, in 1714, just a few years later, that, on the death of Queen Anne (despite having had seventeen pregnancies, she had no heirs), the crown went to her German cousin, George the Elector of Hanover – Handel's former boss. Hence the famous story of his writing The Water Music in 1717 as a way to regain the new king's favor.

Written later in his career, during the reign of George II, Handel's song “Look down, Harmonious Saint” became a short secular cantata in 1736 (setting a text from an Ode to St. Cecilia, the Patron Saint of Music). It may have been originally intended for the choral ode, “Alexander's Feast,” but was added to the “Feast's” 1736 Covent Garden performance when the latter proved too short for a full evening's entertainment. It famously also required a number of instrumental concertos inserted into the lot to make a complete go of it.

Chronologically the last of our creative personalities on the program is also the token female on the list – not surprising, given the times and culture, despite the number of queens who ruled England during these years. Mary Wortley (a.k.a. Lady Mary Wortley-Montagu) – a name I was completely unfamiliar with until I saw this program's musical menu – had in her day a presence far more interesting to our own than one might expect, given the slender verse by which she's represented, so please excuse the digression.

While she was a girl growing up in her family's grand houses, she gave herself an education usually denied women by sneaking into the family library and “stealing” her education “away from the eyes of a despised governess. By the time she was 16 she had written two volumes of poetry, a short novel, and taught herself Latin.”

In London, she became a “popular socialite” at home in both of the “mutually hostile” courts of the present king, George I, and his son, the future George II. In 1715, she contracted smallpox and nearly died – her brother did not survive. The following year, her husband was appointed the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

Writing over the history of these years, I was struck by a few facts given our own time today. As we approach the anniversary of the “Attack on the Capitol” on January 6th, I am reading about Elizabeth's house spy Robert Cecil who uncovered plans to blow up Parliament in the Gunpowder Plot of which Guy Fawkes, in charge of the explosives was only one of a dozen named conspirators attempting to assassinate James I and place his 9-year-old daughter on the throne as a Catholic queen. There was the Great Fire of London in 1666, which I'm reading about while watching news reports of the fire in Boulder, Colorado; and of course the Plague of 1665 as we continue to reel our way into a third year of the Covid-19 Pandemic. But this, I must admit, is the strangest and most unexpected parallel which I cannot help but mention:

While living in Constantinople, Lady Mary Wortley-Montague's own family was afflicted by smallpox and she “was pleased to discover inoculation against smallpox was widespread in the Ottoman empire. The method was to introduce the smallpox virus to an uninfected person, thereby providing immunity from the disease. Lady Mary had the British Embassy’s surgeon inoculate her young son.

“Back home in 1721, while a global smallpox epidemic was killing people from Britain to Boston, she had him inoculate her daughter (born in Turkey), and publicized the benefits of inoculation against bitter hostility, including physical violence. Opponents of the procedure derided it as oriental, irreligious, and a fad of ignorant women, so Lady Mary's fame for it was both mixed and short-lived.”

While art may be timeless and inexplicably connect us through the ages, there is also something to be said for history (especially since Art is not created in a vacuum), even if it's only an adaptation of another quote about history repeating itself (whether we ignore it or not). It may be a more serious note to end this post, considering the cabaret nature of the program and its focus on love, and the parallels between The British Orpheus and the figure of Greek Mythology – let's not forget, in the end, Orpheus was torn to pieces by a band of roving (not to mention, raving) Maenads, his body parts thrown into the river, his head continuing to float downstream, still singing. After all, music also has the power to bring us together and give us strength and hope.

- Dick Strawser

No comments:

Post a Comment